Proyectos de investigación | Namibia

Proyecto de investigacion

Projet de recherche | - 25 de mayo de 2011

Projet de recherche | - 25 de mayo de 2011

Self Determination, Education, and Indigenous Rights:

A multi-sited action research approach

Self-determination is about making informed choices and decisions and creating appropriate structures for the transmission of culture, knowledge and wisdom for the benefit of each of our respective cultures. - Coolangatta Statement Article 3.5

In recent years, a handful of regional surveys exploring the status of San groups across southern Africa have clearly demonstrated that San communities have the lowest socio-economic indicators of any group in southern Africa, are the victims of severe social stigma and participate only marginally in mainstream institutions. Evaluations of indigenous rights and human rights issues for San communities, both before and after the passing of the UNDRIP in 2007, have found that there is a tremendous gap between international ideals and local realities. These works have explored various aspects of rights issues including education, health, gender, intellectual property rights, and land rights.

In international documents addressing indigenous peoples rights, education is recognized as central to the issue of self-determination. This is usually interpreted by governments and other parties to mean the right to access mainstream / formal education, as provided by the state. However, focusing entirely on access to formal education sidesteps the key relationships between education, language, culture and self-determination. My research is grounded in this field that defines the right to education broadly as the right of indigenous communities to determine their own methods of social reproduction.

Most San communities live in more than one country; many of these live on both sides of the border between Botswana and Namibia. This study compares these two countries, identifying where common cultural, historical or socio economic factors lead to common configurations in access to indigenous rights, and in particular in approaches to education and indigenous knowledge. Equally important are the differences between the two – profound differences in cultural composition, historical trajectory, and current political and economic structures of these neighboring countries.

For example, both countries are profoundly affected by the legacy of apartheid, which colors all discourse having to do with minority rights in southern Africa. Mother tongue education is a particularly sensitive area. However, Botswana was never under an apartheid government (they and played an important role in resisting that regime) while Namibia is a former South African colony. These differences result in dramatic differences in policies involving mother tongue education, for example. My study will develop axes of comparison for Botswana and Namibia, focusing in particular on the following categories:

- Educational Rights : This central aspect of my study links education to broader social realities, including actual opportunities for livelihood in areas where Sam communities live, and access to political and other legal processes. What skills do San communities need in order to gain access to their rights? To participate in decision making processes? To survive? Are these skills available through the formal education system, or are other options necessary? This research will integrate an exploration of indigenous knowledge, and how it relates to economic and subsistence opportunities for San communities.

- Implementation of international mechanisms. The UNDRIP and other mechanisms for indigenous rights are generally considered the responsibility of governments. What characteristics lead to an interpretation of the UNDRIP as something that a country must act upon, vs. something that is not a governmental concern? What legal mechanisms allow indigenous communities and local NGOs to take legal action when indigenous rights are violated? How does the general interpretation of “indigenous” and its associations impact legal decision-making processes?

- Access to decision-making processes. Decisions that affect the rights and livelihood of San communities are made at many different levels. These include policy decisions, legal cases, decisions by international donors about where to funnel resources, and by local NGOs about what areas to target. What are these formal and informal decision making mechanisms, and do San communities affected by them have access to these discourses? This study will also examine the role of international corporations and organizations, and the ability of communities to negotiate their rights with these powerful development actors.

Datos

Données générales | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Données générales | - 13 de mayo de 2011

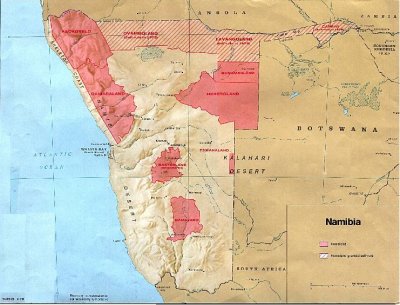

Namibia is located just north of South Africa, on the Atlantic coast of southern Africa. It borders Angola and Zambia to the north, and Botswana to the east. Most of the country is covered by desert, including the Namib on the coast (for which the country is named) and the Kalahari. The population of Namibia is approximately 2.1 million people, with one of the lowest population densities in the world (2.6 / km2). The official language is English, which is the mother tongue of about 7% of the population.

- Map of Namibia, source : Geographic Guide

- http://www.geographicguide.com/afri…

In comparison with most African countries, Namibia is relatively prosperous, has a diversified economy, is democratic, and is reasonably able to meet the needs of its population. However, the country has one of the world’s most unequal income distributions, with 5% of the population managing 50% of the wealth (UNDP 2008). There are thus a large number of poor and marginalized communities in Namibia. By all standards, however, the poorest and most marginalized are the San, who descend from the original occupants of the land.

Ethnic composition

Namibia is an ethnically and linguistically heterogeneous country, with eleven major ethnic / language groups residing within its borders. The largest of these is the Ovambo, who currently are dominant politically, being the main ethnic group associated with the ruling political party (SWAPO, see below). The Ovambo comprise several smaller ethnic groups / dialects; together these groups make up about 50% of the population. Other Bantu-speaking ethnic groups include the Kavango (9%) and the Herero (7% including the Himba, see below), with small percentages of Caprivian, Hambukushu, and Batswana. About 6% of the population is of European descent, including primarily German-, English-, and Afrikaans-speaking peoples.

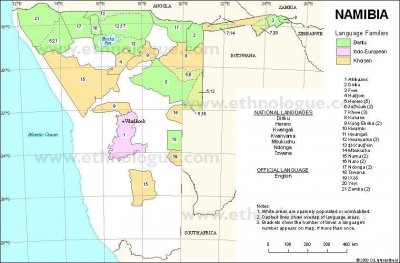

The San, also commonly referred to in Namibia as “Bushmen”, are commonly regarded as the descending from the original inhabitants of the area, hunter-gatherer peoples who occupied the region for at least 30,000 years. Estimates of their numbers in Namibia range from 27,000 to 44,000; the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa uses the figure 38,000, or about 2% of the population. The ethnic category “San” is counted as one of the eleven noted above, but in fact includes several diverse language groups. These include: Ju|’hoansi and ‡X’ao||’aesi (closely related groups, sometimes referred to jointly), !Xun (also closely related to the previous two) Hai||om, Khwe, Naro, and !Xoon (see map, below, and in Language, Culture and Education).

By all measures the San are the most marginalized population in Namibia, have the highest poverty rates and are in most areas highly stigmatized (see UNDP 2008; Suzman 2001).

The Damara (7%) and Nama (5%) populations are descended from semi-nomadic pastoralists who entered into the region about 2000 years ago. Sometimes referred to as Khoe or Khoi, these groups are also often considered indigenous. Related groups in South Africa are mobilizing around this category; this is not happening to the same extent in Namibia. Although the Nama and the Damara suffer from many of the same hardships as the San, as a group they are unquestionably stronger politically and economically, and do not experience the same level of discrimination as the San. The Khoekhoegowab language, spoken by both groups, has been fully developed and is in use as a language of education.

The Himba. Another group often classified along with the San as “marginalized” are the Himba, nomadic pastoralists living in the north-west area of Namibia (the Kunene) and numbering approximately 25,000 people. The Himba are often considered as facing similar challenges to San. Unlike the San, however, the Himba have been able to engage the government much more effectively with regard to the protection of their rights and interest. They have retained strong traditional leadership structures, which have been recognized by the Namibian government, and have maintained effective control over land and natural resources. They are linked politically with the powerful Herero tribe and speak the same language, thus giving them access to information in one of the recognized languages of the country and to mother tongue education. They have also been described as one of the (physically) healthiest communities in Namibia. However, a serious challenge to their autonomy and environment is presented by the on-going threat to erect a large dam at Epupa Falls in northern Namibia, which would displace hundreds of Himba and disrupt their traditional way of life.

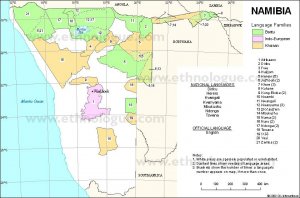

- Map of Namibian Languages, source : Ethnologue

- http://www.ethnologue.com/show_map….

Political / Legal System

The government of Namibia is a presidential representative democratic republic; the president is head of state and head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government, and legislative power is shared by the government and two chambers of parliament; the judiciary is independent of both the executive and legislative.

The two chambers of parliament are the National Assembly, which is the primary legislative body, and the National Council which plays an advisory role. The 78 members of the National Assembly are elected for 5 year terms, 72 voting members are elected by proportional representation, and 6 non-voting memebers are appointed by the president. From 2000 – 2010 there was one San member of the National Assembly, Royal Kxao |Ui|o|oo.

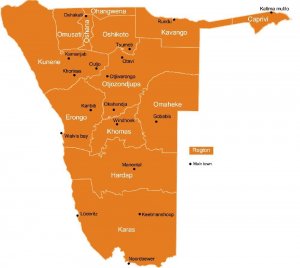

Namibia is divided into 13 administrative regions (see map below); these regions are further divided into a total of 107 constituencies. The 26 members of the National Council are directly elected, for 6 years, by their constituencies. There is one San Regional Councillor, Kxao Moses ‡Oma, representing the Tsumkwe constituency of the Otjozondjupa Region. He was elected in 2004 and re-elected in 2010.

- Map of Namibian Regions, Source: Namibia Nature Foundation

- http://www.nnf.org.na/SKEP/skep_pge…

Namibia is a multi-party system; however it is dominated by the party that formed from Namibia’s liberation movement, the SWAPO Party of Namibia. SWAPO won 75% in the most recent (2009) presidential elections. The newly formed (2007) party Rally for Democracy (RFD) gained 11 percent of the votes in the 2009 elections; the rest of the vote was split between 12 other parties none of which received more than 3% of the vote. Both of the San representatives in Parliament described above are members of SWAPO; however, the San are considered in general to be not strongly affiliated with SWAPO (in part because of their participation on the South African side during the war for independence).

The Traditional Authorities Act of 2000 provides for the establishment of traditional authorities and the designation, election, appointment and recognition of traditional leaders in Namibia. The traditional authorities can make decisions about civil cases according to customary law, as long as it does not contradict the constitution of Namibia. Five San communities have a recognized Traditional Authority (TA); a sixth (the Khwe) are presided over by the TA of a neighboring group and is currently fighting for the recognition of their chief (see Rights, law and Politics)

- Ju/’hoansi Traditional Authority Tsamkxo ≠Oma (“Cheif Bobo”) on right. Photo by: Trine Wengen, Source: Kalahari Peoples Network

- http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/arti…

Namibia was first country in the world to incorporate the protection of the environment into its constitution, and is well-known for its Communal Wildlife Conservancies in which natural animal resources are managed by local communities. The first of these to be established in 1998 was the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, controlled by the Nyae Nyae Ju/’hoansi, a San group (see also Land, Territory and Resources).

The combined effect of the Traditional Authorities Act and the existence of conservancies is that some San communities (especially in the Tsumkwe district) have a measure of autonomy and the ability to live in a manner close to their traditional lifestyle if they choose to. However, most San are living outside of conservancies, often as farm workers in isolated groups.

Namibia is monist; international treaties that they sign automatically become a part of national law (in theory). This means that the UNDRIP, for example, is (in theory) automatically ’domesticated’ even though it is non-binding. Namibia is in the process of determining how best to implement the UNDRIP, and is also considering signing the ILO 169, which is binding (see also Rights, law and Politics).

Socioeconomic Indicators

Health

As in most parts of southern Africa, HIV rates are high, estimated at 13% among the adult population and infection rates for associated diseases like tuberculosis (TB), including the multiple-drug-resistant variety (MDR-TB) are also high. Malaria also presents serious health threats, especially in the northern parts of the country. The average life expectancy for the country is estimated for 2011 at 52 years (CIA World Factbook; World Health Organization).

The international NGO Health Unlimited has identified tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV / AIDS as the most pervasive health problems common among San communities. The specific rate of HIV infection for the San is not known. Previously the Ju/’hoansi in Botswana and Namibia were found to have a much lower rate of infection; this was attributed to women’s stronger negotiating power (Lee and Susser 2002). This is not generalizable to other San groups; furthermore increasing interaction with other groups, economic vulnerability and alcohol use appear to be leading to rising rates of infection in all San communities.

Alcohol abuse also creates and exacerbates health problems in many San communities. As is the case for peoples elsewhere in the world facing these challenges, in San communities alcohol abuse both results from and compounds their already dire situation. Thus far there has been no concerted effort to address these problems. In some places, San are still paid with alcohol for piecemeal work.

Traditional healing practices involved a dance in which the healer entered into a state of trance in order to restore both physical health, and communal well-being. A strong faith in their own healing traditions is still maintained among many San communities and is often used in complement with Western medicine (when this is available). Although this is positive, access to modern health care, and information about modern diseases, is currently vastly inadequate for most San communities.

- Healing Dance, Nyae Nyae (1950’s), Photo: John Marshall, Source: The TFI Reframe Collection

- http://reframecollection.org/films/…

Education

Education in Namibia is compulsory between the ages of 6 and 16, and the country has a high rate of education for Africa with an approximately 86.5% enrollment rate for primary education (grades 1-7) and 49% for secondary education (8-12) (Sacmeq). San students have much lower rates of participation, from 67% in lower primary it drops dramatically from upper primary, with less than 1% enrolled at the highest level, senior secondary (see Language Culture and Education). The literacy rate for the entire country is estimated to be 85% (CIA World Factbook); there is no data specifically for San communities but the literacy rate is far lower, like the general education levels.

Poverty

Unemployment in Namibia is estimated at 51%; thus there are many with school certificates who remain unemployed. According to some estimates, approximately half of the population lives below the poverty line (Human Development Index; CIA World Factbook).

The UNDP gives lower figures for the rate of poverty, but they are disaggregated by ethnic group. According to the UNDP, almost 28% of the population lives below the poverty line, with 14% classified as “severely poor”; the San have the highest incidences of poverty, respectively 60% and 29% ( UNDP 2008). This provides an indication of the relatively greater poverty of the San, in a country that already has a high proportion of poor citizens.

Contexto regional

Contexte régional et international | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Contexte régional et international | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Namibia was the most recent African country to receive independence, from South Africa, in 1990. Formerly known as Southwest Africa, Namibia was a German colony from 1884 until after WWI, when South Africa was mandated to administer the colony. When the mandate was revoked in 1966, South Africa defied the UN and continued to administer the colony.

Also in 1966, the South West Africa Peoples Organization (SWAPO) began engaging in guerilla attacks on the South African forces, beginning a war for independence that lasted for over 2 decades. In this war, some San groups, especially the !Xun and the Khwe, were recruited as trackers for the South African Army, fighting against SWAPO. After South Africa lost the war and Namibia gained independence, the South African government offered ’refuge’ for former soldiers and their families. There are now about 1,100 !Xun and 3,500 Khwe originally from Namibia, now living in one settlement in Platfontein, South Africa.

Namibia is closely linked economically to South Africa, and its currency (the Namibian dollar) is pegged to the South African Rand. Namibia has a very small military, and a fairly fragile economy, highly dependent on mineral extraction, although over half of the population survives through subsistence farming. Relationships with its neighboring countries are thus very important.

Today Namibia is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which grew out of the organization of Frontline States, coordinated around resistance to apartheid. Following the independence all the southern African countries, the objective of the organization shifted towards economic integration.

- Member countries of SADC, Source: The World Bank

- http://web.worldbank.org

Namibia also belongs to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is an economic association promoting regional and international integration of the southern African economies. The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) links Namibia with its closest neighbors, Botswana, South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland in a single customs territory, facilitating market relations and travel between these countries.

History and Indigeneity

The system of apartheid in South Africa and (now) Namibia forced a correlation between ethnic identity, language, and territory (‘homelands’). The apartheid system has been abolished in Namibia; however some effects remain. These include an enormous income disparity – one of the highest in the world – and the populations who benefited from the apartheid system continue to control large portions of the wealth today.

On the other hand, the apartheid system has also meant that some San groups retained access to some of their traditional lands (see also Land, Territory and Resources). The apartheid system also encouraged the development of mother tongue education materials, which has resulted in the use of some San languages for mother tongue education (see Language, Education and Culture).

- Former ”Homelands” in Apartheid Namibia, Source: Mappery

- http://mappery.com/map-of/Namibia-H…

At the regional level, the apartheid history has created in southern Africa profound distrust of indigenous rights arguments, which are understood as suggesting segregation or “separate development.” Understanding this dynamic is crucial to the development of effective approaches to indigenous rights at local, national and regional levels.

The debate over indigeneity in southern Africa has played a leading role in debate over the concept in general, from within anthropology and related disciplines. One argument has been that the term has the potential to be misappropriated or otherwise misused. Some feel that using the category to substantiate claims of mistreatment, or to demand rights of certain peoples, has the potential to create backlash from African governments who are hostile to application of this term to a limited group of people.

Africa

In general, the concept of ’indigeneity’ is perceived as problematic in Africa, and many countries claim that all of their citizens are indigenous in relation to European colonialists. However most peoples claiming indigenous status in Africa are making claims relative to in-migrating agricultural peoples who are also African. However, the current crisis of many indigenous Africans is becoming one not only of exclusion from agriculturally-based political systems, but also new threats posed by industrial economic activities, including mining and new forms of agriculture (see Crawhall 2011).

The African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) has a specific Working Group on Indigenous Populations / Communities in Africa (WGIP) which was active in support for the UNDRIP and which has a Resolution on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

On February 4, 2010, the ACHPR ruled in favour of the Endorois, an indigenous group in Kenya, condemning their expulsion from their traditional land for tourism development as a violation of their human rights. This landmark decision is expected to impact future land rights cases in southern Africa.

Terminology and categories of indigeneity in southern Africa

In general, most groups prefer to be referred to by their own group names where possible. The terms referring to broader categories of indigenous peoples in southern Africa all originate from terms given by outsiders, most of which were initially derogatory, but most of which have also been reclaimed to some extent by those who they refer to.

The term San has been adopted by the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) as the preferred overarching term for the hunting and gathering groups indigenous to southern Africa and their descendants today. This term is used by many academics and is increasingly used by San activists at various levels.

The term Bushmen is recognized and widely used in South Africa and Namibia. In Botswana, the term Basarwa is commonly used to refer to these same peoples. None of these three terms is really better or worse than the others; all have derogatory origins, yet all have been reclaimed to a certain extent by those to whom they refer.

The terms Khoe or Khoi are both used to refer to the descendants of semi-nomadic pastoralists who are also considered indigenous to southern Africa (these groups were formerly referred to as the Khoikhoi, and by the term Hottentot, which is considered very derogatory and no longer used). Khoe groups are in general much more assimilated than San groups, in large part because of the process of forced assimilation during the apartheid era in South Africa, when members of Khoe language and cultural groups were identified with the ‘coloured’ category. Today, especially in South Africa, they also face discrimination and are struggling for recognition of their identity.

The term Khoisan was coined as a linguistic classification of interrelated click languages, and is still often used when discussing language issues. However, for discussing social groups, the preference of southern African organizations is to separate the terms into Khoe and San, or the variation KhoeSan, which acknowledges both the unity and distinctness of the two groups.

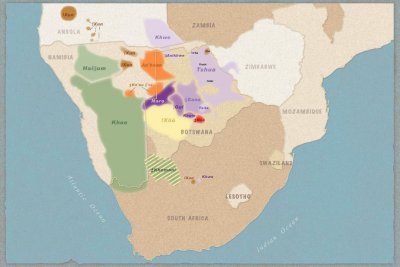

In Botswana and Namibia it is the San / Bushmen / Basarwa who face the greatest social, political and economic problems and who are the main focus of indigenous rights efforts. The distribution of San-speaking populations is indicated in the map below.

Derecho

Droit et politique | - 17 de mayo de 2011

Droit et politique | - 17 de mayo de 2011

Indigenous Status in Namibia

Namibia does not recognize indigenous status in the constitution. Unofficially, it is widely recognized (even among government officials) that certain groups of Namibians: 1) are descended from those who lived there first and 2) are more disadvantaged than others, and 3) that the term “indigenous” applies best to be them. These people are generally understood to be the San, though the Damara, Nama, and Himba are sometimes also considered indigenous (see General Facts). Officially, however, the interpretation of “indigenous” includes all those who are native to the country and is not considered useful as a definition.

International Conventions

Namibia is monist; international treaties that they sign automatically become a part of national law. This means that the UNDRIP, for example, is (in theory) automatically ’domesticated’ even though it is non-binding.

Namibia has signed the UNDRIP after initially spearheading the “Africa Group” in its opposition in 2006. The primary protests were over the privileging of a specific group of Namibians, and fears that the right to “self-determination” could be interpreted to mean the right to secession from Namibia. Following a year of negotiations and consultations, Namibia and the rest of the Africa Group signed the UNDRIP in 2007 (see Crawhall 2011).

Namibia has not ratified ILO 169, however there has recently been some discussion and it is possible that Namibia will sign it in the near future. The Legal Assistance Centre has promoted this movement, conducting training sessions on indigenous rights, who they apply to, and what they entail (see also section on ODPM, below)

Namibia is a signatory of the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights which states that:

"All peoples shall have the right to existence. They shall have the unquestionable and inalienable right to self-determination. They shall freely determine their political status and shall pursue their economic and social development according to the policy they have freely chosen."

Namibia is also a signatory of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In 2009, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published General Comment No. 11: Indigenous Children and their Rights under the Convention, which outlines the ways in which the CRC should be applied to indigenous children and emphasizes that special strategies might be needed.

Namibian Constitution and Legislation

Affirmative action for “persons within Namibia who have been socially, economically or educationally disadvantaged by past discriminatory laws or practices” is guaranteed in Namibia’s constitution (Article 23) and is generally accepted within the country. An argument calling upon this constitutional right is generally considered a more effective than an approach using “indigenous” as the relevant category (see also quote in section below).

The Traditional Authorities Act (2000) allows a community to designate one person to be their traditional authority – who is then approved by the Prime Minister. The community is understood to be an entity sharing a common language, culture and heritage. To be a part of a community one has to a) self-identify and b) be accepted by the rest of the community. Traditional Authorities (TA) can make decisions about civil cases according to customary law, as long as it does not contradict the constitution of Namibia. If only one group is living in a designated territory, the TA effectively has decision making power over that territory. This is the case in many Wildlife conservancies (see Land, Territory and Resources)

There are six San communities who have chosen a traditional authority; five of these are recognized by the Namibian government:

- Nyae Nyae Ju/’hoansi, East Tsumkwe: 1998 (Tsamkxao =Oma)

- !Xun of West Tsumkwe: 1998 (Jon Arnold)

- !Xoo of Omaheke: 2008 (Sofia Jacobs)

- #Kao -//Aesi of the Omaheke: 2008 (Fredrick Langman)

- Hai//om of Outjo: 2004 (leadership contested)

The Khwe chief Ben Ngobara is not recognized. Refusal of recognition has been linked in the past with the Khwe’s collaboration with the SADF in Namibia’s war of independence (explicit remarks to this effect were made by the then-president Sam Nujoma 2003, although the government denies this today). The Khwe are thus subject to the traditional authorities of the Hambukusu, another group living in the area; this group thus effectively gains control over Khwe land.

The Communal Land Reform Act (2002): provides for the allocation of rights in respect of communal land; to establish Communal Land Boards; to provide for the powers of Chiefs and Traditional Authorities and boards in relation to communal land; and to make provision for incidental matters (see also Land, Territory and Resources)

Participation of indigenous leaders in international Indigenous organizations

San leaders from Namibia have participated in the UN Permanent Forum. Chief Tsamkxao =Oma, Traditional Authority of the Nyae Nyae Ju/’hoansi attended The UNPFII Ninth Session (April 2010), with the head of the San Development Programme (described below). The Namibian government sponsored this trip and chose who would attend.

Namibian Government offices working with San / indigenous issues

The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) started a San Development Programme in 2006, with the specific aim of helping San communities to better integrate into the national economy. In 2011 the Programme is expanding to become a Division in the ODPM. Their emphasis is upon entering more fully into Namibian national life, and not upon cultural maintenance. The category indigenous is specifically not used, as explained by a Namibian government official describing why the Office of San Development Programme does not use the term “indigenous” in their discourse:

"If we use the word indigenous, then everyone wants to be assisted, and that will delay our aid to the primary targets, which are the San. So we are more comfortable with the term most marginalized community. Then we can focus on the San, because they are the most marginalized”

However, this same official, and the San Development Programme in general, are promoting the signing of the ILO 169.

National Institute of Educational Development (NIED) under the Ministry of Education tasked with the development of languages for educational use; the development of Khoi and San languages is a specific focus (see also Language, Education and Culture).

Organizations working with Indigenous rights in Namibia

Regional-level organizations

At the continental level, the strongest mechanisms available for indigenous rights is the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) which has a specific Working Group on Indigenous Populations / Communities in Africa.

The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee (IPACC), based in Cape Town, addresses indigenous peoples issues around the continent. IPACC is a networking organization, and is accredited with the UN Economic and Social Council, the UN Environment Programme, the Global Environment Facility, UNESCO and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

At the southern African level, the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) is the most prominent organization working on indigenous issues. Based in Windhoek, Namibia, it is a regional organization working also in Botswana, South Africa and Angola. WIMSA also has a specific focus on indigenous rights.

Namibian indigenous organizations and NGOs supporting indigenous populations

With support from WIMSA, the Namibian San Council was established in 2006 and is composed of 12 members representing the six organised San traditional authorities (Hai||om, !Kung, Ju|’hoansi, Khwe, Omaheke North and Omaheke South), and San community-based organizations.

The Namibian Support Unit of WIMSA (described above) is the main supporting organization for the Namibian San Council.

The Legal Assistance Centre(LAC) has a project focusing on Indigenous Peoples Rights that includes training on human rights and indigenous rights and advocacy for indigenous communities. The International Labour Organization (ILO) office in Pretoria commissioned the LAC to advise on the training and other needs for the Namibian government and others to effectively work with indigenous rights. The LAC is promoting the signing of ILO 169 in Namibia.

The Omaheke San Trust was created in 1997 and serves the 8 000 San living in Omaheke, implementing development projects and representing them at the local and national level.

The Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN) is a support organization specifically for the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, in the Tsumkwe district of Namibia.

Summary

Despite a fairly progressive approach on the part of the Namibian government and a number of government and non-government organizations working towards their integration into Namibia’s economic and political systems, the San remain marginalized by all measures. Although the legislation and the structures exist for San leadership to participate in both the mainstream democratic system, and the traditional authority structures, this participation remains problematic. The focus on integration, while necessary, does not always mesh with traditional San leadership and economic practices. Stigma by neighboring groups, and by some government officials, also creates barriers to participation in national structures.

Territorio

Terre, territoire et ressources | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Terre, territoire et ressources | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Summary of land situation for San in Namibia

The San are descended from hunting and gathering populations and considered to be the first inhabitants of southern Africa, including Namibia. They lived in small social groupings and utilized resources over a broad territory, with sophisticated resource-sharing networks that provided safety nets during times of scarce resources. Following incoming migrations of agricultural and pastoral groups, and European colonialism, San groups were incorporated into incoming groups and pushed into the most marginal areas; some were the targets of genocidal campaigns.

One of the primary factors creating dependency and marginalization among the San of Namibia today is their widespread loss of land and access to natural resources, especially during the past century of colonial rule. Under the apartheid administration of South West Africa, while most other ethnic groups in the country were granted “homelands” (inadequate as they were), most San found their land subsumed into commercial farming areas, the “homelands” of other ethnic groups, game reserves or national parks.

As their options diminished, San in many areas became progressively more dependent upon others for survival, primarily white farmers, military structures and salaries, or the patronage of communal area farmers. Today the vast majority of San live either in commercial farming areas (close to half) or in communal areas in which they form small minority populations (around 40%). The only area in which the San are granted “customary rights” to their land under existing law is in the Tsumkwe district, former “Bushmanland” (see section below), and this is only a fraction of their former territory.

For San communities on commercial farms, the problem of landlessness has become worse since independence. New labour laws since independence have led to a massive reduction of the numbers of workers on commercial ranches over the past decade, and several thousand San farm workers and their families lost their residency rights in the Gobabis Farms region of Eastern Namibia.

The protection and expansion of land rights and achieving land security is thus becoming a high priority in efforts to ensure human rights for Namibia’s indigenous peoples. There are some options for achieving this, through both resource-management programmes, and traditional authority structures.

CBNRM and Conservancies

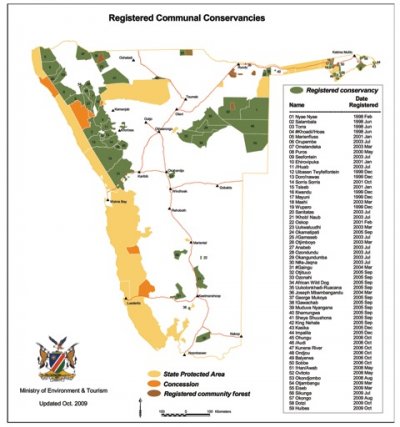

- Map of Conservancies in Namibia, source : Ministry of Environment and Tourism

- http://www.met.gov.na/Directorates/…

An integral part of Namibia’s Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) programme is conservancies, areas of communal land where communities have some control over natural resource management and utilization. With wildlife as a main focus, conservancies provide management units that cover geographically defined areas, and these organizational systems can be extended to encompass other resources including water points, woodlands or forestry, and to address social and economic issues.

The first conservancy established in Namibia was the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in Tsumkwe District East, registered in 1998. This area was formerly the “Bushmanland” reserve under the apartheid government of South West Africa, and later was the site of an integrated rural development effort that began in 1981. The conservancy is supported by a Windhoek-based non-government organization, Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN). The vast majority of their income comes from trophy hunting; other tourism, film-making, crafts and the collection of wild plants also provide income.

- Ju/’hoansi children with skulls from elephants hunted by trophy hunters, Nyae Nyae conservancy. Photo: Jennifer Hays

The only other conservancy in a predominantly San area is N‡a Jaqna, the largest conservancy, established in Tsumkwe District West in 2003. Both the Nyae Nyae and N‡a Jaqna Conservancy face a number of problems, including illegal occupation of their land by other ethnic groups. Support NGOs including the Legal Assistance Centre, WIMSA, and NNDFN (all based in Windhoek) have played important roles in drawing attention to these issues and upholding Conservancy land rights.

The organization Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation(IRDNC) also supports conservancies as a part of their general strategy to help Namibian communities develop sustainable livelihood approaches. Although they are not working specifically with indigenous communities, their work with Khwe, Damara and Himba (and other) communities is based on recognition of traditional knowledge and subsistence strategies.

Conservancies are an innovative strategy on the part of the Namibian government and have a great deal of potential. However, most conservancies have yet to demonstrate substantial long-lasting improvement in the lives of their communities, and thus cannot be considered as a final solution to achieving land and other human rights for the San. Furthermore, only 10% of San currently live in conservancies, and the other 90% are virtually landless.

Relevant Legislation in Namibia: Land and Leadership

Traditional leadership in Namibia is closely connected with land and resource rights. Government structures responsible for overseeing various acts related to traditional leadership, land, and resource rights are spread across several different ministries. There are also a variety of different responsible leadership positions and boards, and a number of different supporting organizations.

The Communal Land Reform Act (2002): provides for the allocation of rights in respect of communal land; to establish Communal Land Boards; to provide for the powers of Chiefs and Traditional Authorities and boards in relation to communal land; and to make provision for incidental matters (see also Rights and Politics; Traditional Authorities Act).

If only one group is living within a given territory, their Traditional Authority effectively has decision-making power over that territory. In such a case, the only way to acquire land within that territory is through the consent of the chief. However, the Communal Land Reform Act limits the amount of land that a chief is allowed to allocate, and sets other restrictions.

Communal Land Boards, established by the Communal Land Reform Act, are under the Ministry of Lands and Resettlement (MLR). Both Wildlife conservancies and Community forest activities (see below) must be approved by Land Boards.

National Wildlife Conservancies (described above), provide communities with control over wildlife resources; these are under the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET). The Conservancy Management is the group of people responsible for the management of a conservancy’s natural resources, and this is separate from the Traditional Authority, or the Communal land boards.

Community Forests allow for community control over plant and grazing resources. These are under the authority of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF), in cooperation with the Namibia Nature Foundation.

The San and National Parks

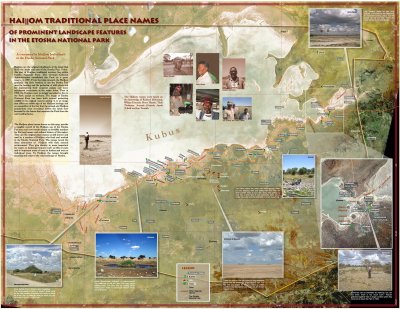

The San in many parts of Namibia also saw their land turned into national parks, to which they then had limited, or no, access. One of the most prominent examples of this is the case of the Hai//om, who were forced to leave their homeland, which had become Etosha National Park, in 1954. Today they are still fighting to gain access to their land. The Xoms /Omis project under the Legal Assistance Center is documenting their history with the park, and their efforts to return to their land.

- Map of Etosha with Hai//om place names, Source: the Xoms /Omis project

- http://www.xoms-omis.org/etoshamaps.html

Bwabwata National Park is the ancestral home of a group of Khwe San, and is an important ecological zone in Namibia (in the western Caprivi). Their right to develop hunting and other tourism ventures on the land has been hampered by land contests and slow government processes, but at the end of 2010 they were granted a tourism concession to develop a lodge within the park.

Khaudom National Park, to the north of Nyae Nyae, is part of the ancestral land of the Nyae Nyae Ju/’hoansi, but today they are not allowed to live there. There have been no legal cases contesting this land.

Subsistence

The San are the poorest group in Namibia (see also General Facts). The vast majority who are employed are working as farm workers, for very little pay – or sometimes only for food and / or alcohol rations. Some are employed by NGOs or as trackers, or in menial labor positions. In some areas, in particular in conservancies, San still rely upon hunting and gathering for part of their subsistence.

San throughout Namibia rely heavily upon government food aid for their survival, as well as pensions. Although there is legitimate concern that this reliance contributes to the dependency of San communities, for many it often provides a needed safety net. Careful evaluation is needed to determine how to provide critical assistance to San communities without furthering a situation of dependency.

Landlessness, a lack of education, social stigmatisation, high mobility, extreme poverty and dependency conspire to prevent San from breaking out of the self-reproducing cycle of marginalisation in which many feel they are trapped (Suzman 2001)

Cultura

Langue, éducation et culture | - 13 de mayo de 2011

Langue, éducation et culture | - 13 de mayo de 2011

General

Namibia is a multilingual country and has a strong focus on cultural rights and on language in education. Namibian educational policy recognizes the pedagogical soundness of mother tongue education during the early years of schooling and is also sensitive to the function of language as a medium of cultural transmission; it also emphasizes the equality of all languages regardless of the number of speakers.

In many ways, Namibia has the most progressive educational approach of all the southern African countries in which San reside. However, the focus of almost all educational efforts, by the government and by non-government organizations, is integration into the formal education system, and assimilation. Despite a variety of concerted efforts at integration, most San students still do not go far in the formal education system. The general reasons cited are problems understanding the language of instruction, stigma and bullying from other students, and cultural mismatch between the home and school (see also Hays 2011). These reported reasons, and a high drop-out rate, are consistent among San communities across southern Africa.

Language distribution

There are three main language families in Namibia. The most dominant are the European colonial languages: English, German and Afrikaans (based on Dutch). These are the only languages for which mother tongue education is available throughout the school years. The most widely-spoken are the Bantu languages, spoken as a mother tongue by the majority of the population; eight of these are available as languages of instruction for the first three years. The third language family is that of Khoi-San languages, spoken by the descendants of hunting / gathering and herding populations that are generally considered “indigenous” to Namibia. Only one (Ju/’hoansi, see below) is available as a language of education for the first three years, and this is limited to one community.

- Map of Namibian Languages, source: Ethnologue

- http://www.ethnologue.com/show_map….

School attendance and San

In Namibia, enrollment rates for the ethnic groups are calculated according to home language, self-identified by learners, and the category “San” is included in the list. According to the most recent available statistics for 2008, the enrollment rate for San is 67% in Lower Primary phase (grades 1-3). This drops to 22% in the upper primary phase (grades 4-7), and then to 6% for the junior secondary (8-9) and less than 1% at the senior secondary level (11-12). As these statistics show, the number of San learners decreases dramatically in the higher grades. This extremely high drop-out rate is far above national average, and is especially high among female San learners (See Davids 2011).

Languages policy and language in education

The official language of Namibia is English, and it is compulsory to teach English in the lower primary phase (grades 1-3), and to use it as a language of instruction from grade 4. Article 3 of the Namibian Constitution guarantees the right to use a language other than English as the medium of instruction. Article 19 of the Namibian Constitution guarantees the cultural rights of people.

The Namibian Language Policy for Schools allows for the mother tongue to be used as the medium of instruction during the first three years of schooling, and that each language community can decide on the medium of instruction for their children in this phase. It also stipulates that the first language should be taught as a subject throughout the years of formal education.

Namibian language policy states that “all national languages are equal regardless of the number of speakers or the level of development of a particular language.” Currently ten African languages are developed and used for instruction. These include:

- Ju|’hoansi (the only San language),

- Khoekhoegowab (spoken by the Nama and the Damara),

- Otjiherero (a Bantu language spoken by the Himba, as well as Herero),

- Seven other Bantu languages (Oshikwanyama, Oshindonga, Rumanyo, Rukwangali, Setswana, Silozi and Thimbukushu)

Although in theory speakers of these ten languages have access to mother tongue education, in practice it is not guaranteed and it depends on other factors.

In addition to Ju|’hoansi, two other San languages, !Xun and Khwedam, have orthographies and dictionaries and some educational materials have been developed. However, the implementation of language and education policy for these languages is very limited and depends to a great extent upon international donors and non-government organizations (See Davids 2011).

- Ju|’hoansi Teachers Hansi |Kaeche and ǂOma N!ani with their students at ǂOtcaqkxai Village School, Photo: Jennifer Hays

For all San languages, including Ju|’hoansi, the lack of development of the language and the lack of trained and qualified teachers complicate their provision in schools. Although there is support for San teachers in the national teacher education programs, San student teachers have a much lower success rate than students from other ethnic groups.

In the Ministry of Education document National Policy Options for Educationally Marginalized Children (2000), San children are recognized as one of the three most marginalized groups: San, Himba, and the children of farmworkers, very many of whom are San (later the categories of disabled children and orphans were also added to this list). This policy document emphasizes flexibility, noting that “It is necessary to use a number of unconventional approaches in order to achieve education for all educationally marginalized children.”

There is therefore room in Namibian policy for alternative education approaches. In practice, this is limited by the tendency of governments to standardize educational approaches, and the requirements of donors to support projects that fit within the government system.

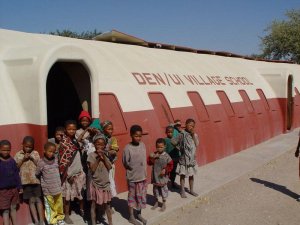

Indigenous Education Projects

The openness and flexibility of Namibian educational policy allowed for the development of the Village Schools in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy of Tsumkwe district, in northeastern Namibia, where San teachers teach Ju|’hoansi children in their own language up until grade 3. This is the only place in the country where San children have mother tongue education. However, even the village schools student have an extremely high dropout rate from the local government schools, which they enter in grade 4 (see Cwi and Hays 2011). In 2004 the Village Schools transitioned from an alternative project to government schools; teachers are now thus required to obtain the standard teaching certificate; most Ju/’hoansi teachers do not succeed in the training programs.

The Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) has a focus on early childhood education in the mother tongue, with the introduction of English, that prepares young children to enter into the formal school system (See Haraseb 2011). It is still to early to tell whether this will increase the retention of San students in primary school, and beyond

Culture and subsistence

The San are traditionally hunters and gatherers, and knowledge of the “bush” was critical to survival, and was passed down through generations effectively, for millennia. Today, access to modern education is necessary for participation in national political, economic, and social systems, and for many types of employment. However, traditional skills are also still very important.

Most San that are employed today are at the bottom of the economic hierarchy, as farmworkers or other low-paid manual labour. In places where they still have access to land, such as conservancies, their traditional skills in fact provide some of their best options for both subsistence and employment. Where possible, many San still rely to a large extent on bush foods – even if it is not the only, or even primary, source of food.

Income from tracking for big-game hunters and for wildlife conservation efforts is also an important source of income; options for building on this further are being discussed by the Namibian Qualifications Authority and relevant NGOs. Income from plant sources is also important, in particular devils claw (exported as an arthritis treatment) and Hoodia (sold as an appetite suppressant, see below). However, incomes from both plant and wildlife sources are threatened by groups who invade their land and also by agricultural developers (see for example article about Bwabwata National Park)

Cultural rights

In 2000, the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) drew up the Media and Research Contract for the San of southern Africa. This contract, now being honoured by the majority of researchers and media workers, requires that all researchers and media representatives who work with the San must respect the cultural heritage of the San, and must not use information, images or recordings obtained from them without permission.

In 2003 South African courts upheld the right of San communities to share profits gained from the sale of an appetite-suppressing drug developed from the Hoodia gordonii plant. This “victory” has led to an increased interest in traditional knowledge, both within and outside of San communities. In Namibia some San are involved in many government-supported initiatives encouraging the use and development of Hoodia and other natural resources in the country. To help San communities understand how best to approach new developments in this area, the Handbook on San Intellectual Property Rights was also produced by WIMSA in 2004 and distributed to San communities. Continued vigilance will be necessary, however, to ensure that the cultural knowledge of the San is not exploited for the gain of others.

Versión imprimir

Versión imprimir