Aires de recherche | Botswana

Projet de recherche

Projet recherche | - 6 avril 2011

Projet recherche | - 6 avril 2011

Self Determination, Education, and Indigenous Rights :

A multi-sited action research approach

Self-determination is about making informed choices and decisions and creating appropriate structures for the transmission of culture, knowledge and wisdom for the benefit of each of our respective cultures. - Coolangatta Statement Article 3.5

In recent years, a handful of regional surveys exploring the status of San groups across southern Africa have clearly demonstrated that San communities have the lowest socio-economic indicators of any group in southern Africa, are the victims of severe social stigma and participate only marginally in mainstream institutions. Evaluations of indigenous rights and human rights issues for San communities, both before and after the passing of the UNDRIP in 2007, have found that there is a tremendous gap between international ideals and local realities. These works have explored various aspects of rights issues including education, health, gender, intellectual property rights, and land rights.

In international documents addressing indigenous peoples rights, education is recognized as central to the issue of self-determination. This is usually interpreted by governments and other parties to mean the right to access mainstream / formal education, as provided by the state. However, focusing entirely on access to formal education sidesteps the key relationships between education, language, culture and self-determination. My research is grounded in this field that defines the right to education broadly as the right of indigenous communities to determine their own methods of social reproduction.

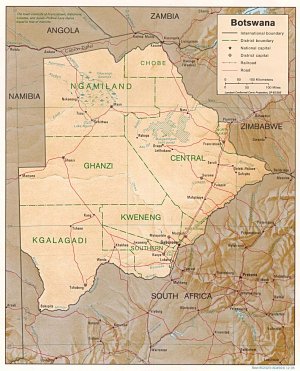

Most San communities live in more than one country ; many of these live on both sides of the border between Botswana and Namibia. This study compares these two countries, identifying where common cultural, historical or socio economic factors lead to common configurations in access to indigenous rights, and in particular in approaches to education and indigenous knowledge. Equally important are the differences between the two – profound differences in cultural composition, historical trajectory, and current political and economic structures of these neighboring countries.

For example, both countries are profoundly affected by the legacy of apartheid, which colors all discourse having to do with minority rights in southern Africa. Mother tongue education is a particularly sensitive area. However, Botswana was never under an apartheid government (they and played an important role in resisting that regime) while Namibia is a former South African colony. These differences result in dramatic differences in policies involving mother tongue education, for example. My study will develop axes of comparison for Botswana and Namibia, focusing in particular on the following categories :

- Educational Rights : This central aspect of my study links education to broader social realities, including actual opportunities for livelihood in areas where Sam communities live, and access to political and other legal processes. What skills do San communities need in order to gain access to their rights ? To participate in decision making processes ? To survive ? Are these skills available through the formal education system, or are other options necessary ? This research will integrate an exploration of indigenous knowledge, and how it relates to economic and subsistence opportunities for San communities.

- Implementation of international mechanisms. The UNDRIP and other mechanisms for indigenous rights are generally considered the responsibility of governments. What characteristics lead to an interpretation of the UNDRIP as something that a country must act upon, vs. something that is not a governmental concern ? What legal mechanisms allow indigenous communities and local NGOs to take legal action when indigenous rights are violated ? How does the general interpretation of “indigenous” and its associations impact legal decision-making processes ?

- Access to decision-making processes. Decisions that affect the rights and livelihood of San communities are made at many different levels. These include policy decisions, legal cases, decisions by international donors about where to funnel resources, and by local NGOs about what areas to target. What are these formal and informal decision making mechanisms, and do San communities affected by them have access to these discourses ? This study will also examine the role of international corporations and organizations, and the ability of communities to negotiate their rights with these powerful development actors.

Données

Données générales | - 11 avril 2011

Données générales | - 11 avril 2011

General Facts

Botswana is a land-locked in southern Africa, bordered by South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. 70% of the country, which is about the size of France, is covered by the Kalahari Desert. The Central Kalahari Game Reserve and the Okavango Delta are two prominent features of the country and attract thousands of tourists every year.

The population of Botswana is just over 2 million. The majority of citizens of Botswana (approximately 79%) speak Setswana as a home language. The setswana-speaking population is composed of eight tribes ; the largest group is the ethnic Batswana, who comprise approximately 20% of the nation’s population. The other 7 of the eight major tribes include Bamangwato, Bakwena, Bangwaketsi, Bakgatla, Barolong, Bamalete, and Batlokwa, all of whom have adopted Setswana as their mother tongue. About 11% of the population is Kalanga, who, although a linguistic minority, have high levels of education and employment.

The indigenous hunters and gatherers, known elsewhere as San or Bushmen, are referred to in Setswana as Mosarwa / Basarwa (sg / pl). Exact figures by ethnic group are not available, but estimates of the number of Botswana’s citizens who are are San / Basarwa range from 46,000 – 60,000 (about 2.5% – 3% of the population). (See also Regional Context – Terminology). The San / Basarwa have the lowest socio-economic status in the country, and are the most stigmatized ethnic group (see for example Suzman 2001)

The remaining percentage is composed of a variety of other Bantu-speaking ethnic groups, including Baherero, Wayei, Hambukushu and Bakgalagadi, all of whom live mainly in rural areas and are often living closely with San / Basarwa communities.

In Setswana, prefixes are added to the root -tswana to create specific meanings, like Botswana which literally means “place of the Tswana.” Motswana, and Batswana are the singular and plural terms for people of Tswana identity. Today, these terms are also used to mean “person/people who live in Botswana.” These dual meanings of the term “Batswana,” allow citizenship to be associated with one ethnic identity, despite the fact that there are significant minorities in the country.

The official language is English, and the national language is Setswana. The use of any other languages for education or other official purposes is prohibited by law.

Political / legal system

Botswana is considered to be one of the least corrupt countries in Africa, and one of the most economically stable. They take pride in this and strongly resist pressure from other countries, the UN or other international organizations for reform.

The official political system of Botswana functions primarily with two parallel systems, a Western democratic system, and a system based on the traditional chiefdoms. Within these systems, traditional governance mechanisms of the San are not recognized and their systems are often considered non-existent.

Botswana is a representative democratic republic, with a multi-party system. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) has been in power since the coutry’s independence in 1967. The president is not elected directly by the population, but chosen by the ruling party. The current president Ian Khama (who is the son of Sir Seretse Khama, Botswana’s first president) was chosen by the BDP in September 2009. Legislative power is vested in the Parliament, which includes the president and the National Assembly.

Operating parallel to the National Assembly, and also established at Independence, is Botswana’s House of Chiefs – Ntlo ya Dikgosi – which consists of 35 members. These include 8 hereditary chiefs – also called paramount chiefs – representing Botswana’s dominant tribes (listed above), 22 indirectly elected chiefs and 5 appointed by the president. Currently, there are no San chiefs in Ntlo ya Dikgosi, although there have been in previous years (see also section Rights and Politics)

Parallel to Botswana’s formal court system, and ultimately presided over by the House of Chiefs, is the kgotla system – the traditional system of law based on the village structure. Kgotla meetings are used to decide civil cases and small-scale criminal cases. Important features of kgotla meetings are that anyone who wants to has the right to speak, and that consensus should be reached between involved parties before a final decision is made.

The kgotla system is considered a form of consultation and local decision-making by the government of Botswana ;the suggestion of the UN Special Rapporteur James Anaya that the San in Botswana were not properly consulted was met with this argument. However, while the kgotla is deeply embedded in Batswana traditional culture and hierarchy, it is a foreign system to Basarwa / San communities who often report feeling intimidated in kgotla meetings.

Botswana practices capital punishment and has received pressure from within the country (especially from the local human rights organizations Ditswanelo), and from international bodies ; including the UN Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review to abolish the death penalty. The UPR review of Botswana in December 2008 recommended abolishing the death penalty ; this was rejected by the government. Corporal punishment is legal and flogging is a common punishment meted out in the kgotla system. Corporal punishment is also legal in schools (see Language, Culture and Education)

Botswana is dualist which means that it must domesticate international law. This argument has been used in court to counter a ruling of the African commission on Human and Peoples Rights, even though Botswana is a signatory of the African charter (see Rights and Politics). This fits with Botswana’s general resistance to international pressure and input on their internal legislation.

Socioeconomic indicators

Botswana has one of the highest HIV/AIDS rates in the world. However, following aggressive campaign to reduce mother-to-child transmission and the provision of free anti-retrovirals to all who need them, estimations of life expectancy in the country has gone from 35 – 40 in the years 2001 – 2006 to an estimate of approximately 50 for 2011. (source : World Health Organization)

The specific rate of infection for the Basarwa / San is not known. Previously the Ju/’hoansi in Botswana and Namibia were found to have a much lower rate of infection ; this was attributed to women’s stronger negotiating power (Lee and Susser 2002). Increasing settlement appears to be leading to rising rates of infection, although there are no recent statistics disaggregated by ethnic group.

Other health threats include an emerging prevalence of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and malaria ; these diseases disproportionately affect the San and other poor rural populations far from health care facilities in urban centres.

Botswana has an adult literacy rate of 81%, which is high for Africa. A 2010 study estimates the country’s school attendance rates to be also high : 90% for the primary school level, 50% at the junior secondary school level, 20% at the senior secondary and 11.4 % for the tertiary level.

Official breakdown of figures by ethnic group are not available. However, by comparison, a recent (2009) survey by the NGO Thuto Isago Trust found that, for example, among farm workers who are predominantly San, 55-60% of children between 6–15, were not in school (see also Language, Culture and Education). It is considered generally true that the San / Basarwa have a very low rate of participation in Botswana’s school system.

Contexte régional

Contexte régional et international | - 11 avril 2011

Contexte régional et international | - 11 avril 2011

Botswana can be considered within two general regions : the African continent as a whole, and also within the specific context of southern Africa. Approaches to ethnicity within Africa in general are shaped by colonial encounters, and within southern Africa the recent apartheid regime of South Africa and southwest Africa is a strong factor in determining government’s response to the concept of indigeneity.

Botswana – state and identity formation

Botswana, unlike almost every other modern African state, was never a European colony, but a British protectorate. Established in 1885, it was originally expected that the British would turn it over to Rhodesia or South Africa. This never happened, however, due in part to opposition by Tswana leaders ; thus from its earliest stages Botswana’s leaders have maintained a measure of autonomy in the face of international pressure.

The constitution of Botswana was established in 1965, and on September 30 1966, Botswana held its first independent elections, and Seretse Khama became the first elected president. At that time, Botswana was one of the poorest countries in Africa. After the discovery of diamonds in 1967, however, Botswana became one of the fastest growing economies in the world, and today is considered to be one of Africa’s most successful economies.

During the first two decades of its existence as a nation, Botswana was surrounded on 3 sides by apartheid countries – South Africa to the south and South West Africa (now Namibia) to the west and the north ; until 1980 its neighbor to the east was white-governed Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). From 1970 – 1990, Botswana played an important role in the ‘Frontline States,’ formed in 1970 to co-ordinate their responses to apartheid.

Today Botswana is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which grew out of the organization of Frontline States, following the independence all the southern African countries, with the objective shifting towards economic integration.

Botswana also belongs to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is an economic association promoting regional and international integration of the southern African economies. The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) links Botswana with its closest neighbors, Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland in a single customs territory, facilitating market relations and travel between these countries.

Botswana’s relative independence from colonial rule, anti-apartheid leadership, and economic success all contribute to Botswana’s positive self-image and international prestige. Botswana does not easily bow to international pressure, and strongly believes in the integrity of its approach to race / ethnicity, which was formed in opposition to apartheid.

Indigeneity in the African Region

Southern Africa

In southern Africa the system of apartheid forced a correlation between ethnic identity, language, and territory (‘homelands’). Because of this history, today there is profound distrust of indigenous rights arguments, which are understood as suggesting segregation or “separate development.” Understanding this dynamic is crucial to the development of effective approaches to indigenous rights at local, national and regional levels.

The debate over indigeneity in southern Africa has played a leading role in debate over the concept in general, from within anthropology and related disciplines. One argument has been that the term has the potential to be misappropriated or otherwise misused. Some feel that using the category to substantiate claims of mistreatment, or to demand rights of certain peoples, has the potential to create backlash from African governments who are hostile to application of this term to a limited group of people.

Africa

The concept of ’indigeneity’ is perceived as particularly problematic in Africa, and many countries claim that all of their citizens are indigenous in relation to European colonialists. However most peoples claiming indigenous status in Africa are making claims relative to in-migrating agricultural peoples who are also African. However, the current crisis of many indigenous Africans is becoming one not only of exclusion from agriculturally-based political systems, but also new threats posed by industrial economic activities, including mining and new forms of agriculture (see Crawhall 2011).

The African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) has a specific Working Group on Indigenous Populations / Communities in Africa (WGIP) which was active in support for the UNDRIP and which has a Resolution on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

On February 4, 2010, the ACHPR ruled in favour of the Endorois, an indigenous group in Kenya, condemning their expulsion from their traditional land for tourism development as a violation of their human rights. This landmark decision is expected to impact future land rights cases in southern Africa.

Terminology and categories of indigeneity in southern Africa

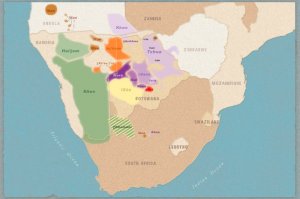

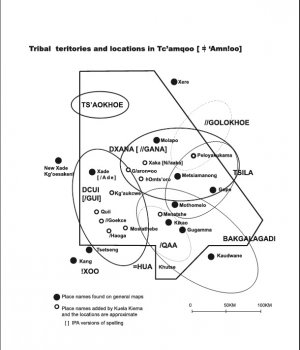

In general, most groups prefer to be referred to by their own group names where possible. The distribution of San and Khoe languages in the region is illustrated in the map below.

JH_Botswana_contexte_regionale_carte B.doc

Source : Letloa Trust (Botswana)

The terms referring to broader categories of indigenous peoples in southern Africa all originate from terms given by outsiders, most of which were initially derogatory, but most of which have also been reclaimed to some extent by those who they refer to.

The term San has been adopted by the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) as the preferred overarching term for the hunting and gathering groups indigenous to southern Africa and their descendants today. This term is used by many academics and is increasingly used by San activists at various levels.

The term Bushmen is recognized and widely used in South Africa and Namibia. In Botswana, the term Basarwa is commonly used to refer to these same peoples. None of these three terms is really better or worse than the others ; all have derogatory origins, yet all have been reclaimed to a certain extent by those to whom they refer.

The terms Khoe or Khoi are both used to refer to the descendants of semi-nomadic pastoralists who are also considered indigenous to southern Africa (these groups were formerly referred to as the Khoikhoi, and by the term Hottentot, which is considered very derogatory and no longer used). Khoe groups are in general much more assimilated than San groups, in large part because of the process of forced assimilation during the apartheid era in South Africa, when members of Khoe language and cultural groups were identified with the ‘coloured’ category. Today, especially in South Africa, they also face discrimination and are struggling for recognition of their identity.

The term Khoisan was coined as a linguistic classification of interrelated click languages, and is still often used when discussing language issues. However, for discussing social groups, the preference of southern African organizations is to separate the terms into Khoe and San, or the variation KhoeSan, which acknowledges both the unity and distinctness of the two groups.

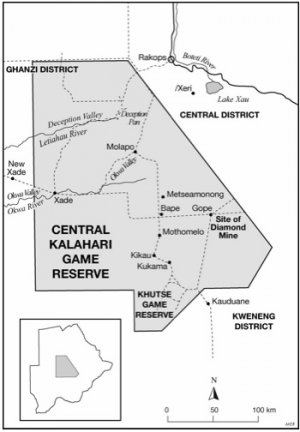

In Botswana and Namibia it is the San who face the greatest social, political and economic problems and who are the main focus of indigenous rights efforts. The distribution of San-speaking populations is indicated in the maps below, for the southern African region and specifically for the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana.

Droits

Droit et Politique | - 11 avril 2011

Droit et Politique | - 11 avril 2011

General

Botswana has an official policy of non-recognition of ethnic minorities, and takes the position that all Batswana (residents of Botswana) are indigenous to the country. There is no recognition of indigenous status in the national constitution.

Signature or Ratification of International Mechanisms related to Indigenous Peoples :

Botswana is a dualist country, which means that it must domesticate international law by incorporating it into national law (as they are in the process of doing with the Convention on the Rights of the Child ; see below). This argument has been used in court to counter a ruling of the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR), even though Botswana is a signatory of the African Charter for HPR (see below).

- Botswana has signed the UNDRIP (after initially being a part of the opposition group led by Namibia). Their signing of the UNDRIP was with the understanding that the term “indigenous” applies to all citizens of the country, and therefore the declaration is not relevant to Botswana.

- Botswana has not ratified ILO 169 and has no plans to do so. Ratification was recommended by the UN Human Rights Committee Working Group on Universal Periodic Review when they reviewed the country in December 2008. Botswana explicitly rejected this recommendation.

- Botswana is a signatory of the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights which states that :

All peoples shall have the right to existence. They shall have the unquestionable and inalienable right to self-determination. They shall freely determine their political status and shall pursue their economic and social development according to the policy they have freely chosen.

- Botswana is also a signatory of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and since 2008 has been in the process of “domesticating” the CRC. Although the convention itself is not specific to indigenous children, in 2009, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published General Comment No. 11 : Indigenous Children and their Rights under the Convention, which outlines the ways in which the CRC should be applied to indigenous children and emphasizes that special strategies might be needed. For example paragraph 80 says :

In order to effectively implement the rights of the Convention for indigenous children, States parties need to adopt appropriate legislation in accordance with the Convention. Adequate resources should be allocated and special measures adopted in a range of areas in order to effectively ensure that indigenous children enjoy their rights on equal level with non-indigenous children.

As a state party to the CRC, Botswana is thus obliged to ensure that San children have access to education in their own language, and that respects their own culture and values. As Botswana proceeds with domestication of the CRC, addressing the specific needs of San children will be an important aspect of educational reform (see also Hays 2011).

Visit of the Special Rapporteur

Botswana invited the Special Rapporteur James Anaya to visit the country in March 2010. In his report, released in June 2010, Anaya applauds the government for their provision of services to remote areas (see Remote Area Development Programme, RADP), but expresses concern about the following areas : Respect for Cultural Diversity ; Participation and Consultation ; and Historical Grievances.

Botswana’s response to the report was that : “All Batswana are indigenous to the country” and that policy, legislation and programmes are guided by aim of building a society that is “genuinely inclusive” and “not discriminating on the basis of ethnic or tribal identity.” They denied the assertion that marginalized communities are not adequately consulted, and referred to the kgotla system. They also stated that Basarwa are allowed to hunt and gather, if they use traditional weapons.

Regional Indigenous and Human Rights Organizations :

At the continental level, the strongest mechanisms available for indigenous rights is the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) which has a specific Working Group on Indigenous Populations / Communities in Africa. Botswana is a signatory of the ACHPR Charter. However, in practice, Botswana does not necessarily accept rulings of the ACHPR.

The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee (IPACC), is a network of 150 indigenous peoples’ organisations in 20 African countries. Based in Cape Town, IPACC addresses indigenous peoples issues around the continent. Their purpose is to unite diverse community based indigenous peoples’ organisations into a network and alliance for effective advocacy and to promote the rights and voices of indigenous peoples at national, sub-regional, African and international levels. IPACC is accredited with the UN Economic and Social Council, the UN Environment Programme, the Global Environment Facility, UNESCO and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

At the southern African level, the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) is the most prominent organization working on indigenous issues. Based in Namibia, it is a regional organization working also in Botswana, South Africa and Angola. WIMSA also has a specific focus on indigenous rights.

Kuru Family of Organizations (KFO), based in Botswana, also has links with WIMSA and IPACC. KFO focuses on the development of economic opportunities, leadership development, and training.

These organizations are extremely important for the support that they provide to indigenous communities in Botswana. None are currently run by indigenous peoples, although training in leadership and capacity building is central to their focus.

None of these organizations has significant influence on government policy towards indigenous peoples in Botswana.

Indigenous Politics and Leaders in Botswana :

Indigenous peoples from Botswana do not participate regularly in the UNFPII or WGIP, and have not attended in recent years. However, there are some increasingly outspoken San leaders on the issue of indigenous rights, both within the officially recognized government structures, and also in NGOs.

First People of the Kalahari (FPK) is a San-led advocacy organization based in Ghanzi, established as a non-government organization (NGO) in 1993 with support from international donors. Roy Sesana took over leadership in 1995 and was an important figure in the CKGR court case (see Land, Territory and Resources).

- Botswana, Gaborone, Roy Sesana (3d from right) and other applicants on the CKGR case December 2006, Photo : Sidsel Saugestad

The Botswana Khwedom Council is a newly established organization that aims to promote the interests of San / Basarwa communities in Botswana. They have a constitution based upon community consultation and aim to work with the government and communities to improve language and education for San, as well as general political participation.

There are officially recognized San chiefs in some areas, elected by their constituencies ; these include Chief Baneka of Pandematenga and Chief Beslag of New Xade, both outspoken advocates of indigenous rights. These two are also among a handful of San chiefs who, in recent years were elected or appointed to the House of Chiefs – Ntlo ya Dikgosi (see also General Facts). These individuals are not, however, seen as representing San, specifically (as, for example, the chiefs of the other “paramount tribes” are). In general, these chiefs and any other San / Basarwa who are in political roles are very limited in their ability to use categories of ethnicity or indigeneity in legal cases. Furthermore, in areas where San live in political constituencies with other ethnic groups, San leaders are rarely elected into office. Since the most recent elections in 2009, there are no San chiefs in the Ntlo ya Dikgosi.

New Developments

The Research Centre for San Studies was opened on April 19, at the University of Botswana (UB). This Centre has grown out of the University of Botswana – University of Tromsø Collaborative Programme in San Research and Capacity Building (known as the UBTromsø Programme), which was initiatied in 1996. The transition to a multidisciplinary research centre at the University is a move to a level of higher profile. It is noteworthy that a research centre devoted to research “with and by the San” was accepted by the various University bodies who had to approve it – even though it could be seen as contradicting government policy. It remains to be seen how this centre will affect the general discourse of indigeneity in Botswana

Territoire

Terre, territoire et ressources | - 11 avril 2011

Terre, territoire et ressources | - 11 avril 2011

Access to Resources

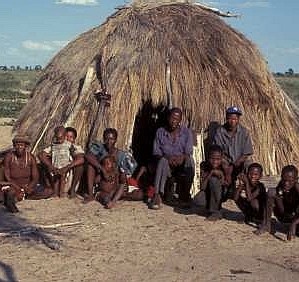

The most important economic resources for the country of Botswana are diamond mining, cattle ranching, and tourism. All of these affect land rights for the San / Basarwa in Botswana ; very few have access to their traditional lands or resources. The majority have been displaced by cattle ranchers, including both White (mainly Afrikaans-speaking) and Black (primarily Batswana, and some Herero) farmers. San families are frequently employed as farm labor, living in small family units and working for very low wages.

A different pattern of land rights concerns have been raised in Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), whose residents have taken the government of Botswana to court twice in the past 5 years (see section below). There have been accusations that the intention to mine for diamonds was behind the government’s relocation of the San from their traditional land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR). The government denies that this is the reason, claiming instead that the people living in the reserve are a threat to the wildlife, and also thus undermining the tourism value of the reserve.

In 1979, Botswana made efforts to ensure that those people who were dependent on wildlife for part of their subsistence had legal rights to hunt in national faunal conservation legislation. In the early part of the new millennium, however, the Special Game Licenses (SGLs) were abolished by the government. Under the new regulations, individuals have to submit a formal request to the Department of Wildlife and National Parks in the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife, and Tourism, or enter into a raffle system. The only other way that people can continue to hunt for subsistence is to be in a community-controlled Wildlife Management Area (CCHA) where a community trust has been formed. People outside of community trust areas it is difficult to get a license and to continue to hunt as they had done. (see Hitchcock et al 2011).

During the Universal Periodic Review by the UN Human Rights Committee’s Working Group on UPR, December 2008, several countries made recommendations about the need to ensure land rights for the indigenous peoples of Botswana ; particularly in relation to the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and diamond mining. In their response, the Government of Botswana rejected these recommendations :

"In the spirit of solving problems amicably among Batswana, the Government is already actively engaged in consultations with all relevant stakeholders. The Government already has a clear and effective policy and land tenure system that addresses issues related to access to land for all Batswana, including residents of the reserve. To this end the Government does not accept these recommendations."

In this quote, the term “Batswana” is used to mean all citizens of Botswana ; this term also refers to people who are ethnically “Tswana” and speak Setswana (see also General Facts)

The Central Kalahari Game Reserve court case

The resettlement of San communities from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) beginning in the 1990s and continuing in various stages until the present time, is the most visible example of land rights violation for San in Botswana (see Saugestad 2011 ; Hitchcock et al 2011).

Established in the early 1960s, the original intent of the CKGR was to be both a wildlife preserve and an area where the San / Bushmen could life traditionally if they chose to. In the late 1980s the government had begun a campaign to encourage people to leave the reserve ; in 1997 the government began resettling CKGR residents to New Xade, to the west of the reserve, and to Kaudwane, on the south-east.

-

- Source : James Workman, 2009, Heart of Dryness. How the last Bushmen can help us endure the coming age of permanent drought, New York, Walker publishing company

In 2002 the government conducted another round of removals, this time with more force, removed all water tanks and sealed up existing wells. Those San who moved back into the reserve risked arrest. Following these removals, with funding from a CKGR Legal Rights Support Coalition, Roy Sesana, of First Peoples of the Kalahari and 242 other applicants brought an application to the High Court of Botswana claiming their right to remain in the territory. After lengthy negotiations and many delays, in 2006 the case went to trial, with lawyers representing the applicants paid for by Survival International.

The verdict in December 2006 was received globally as a victory for the San. The court ruled that the CKGR residents were lawfully in possession of their land, and that the government was wrong to forcibly remove them and to deny them re-entry. The court ruled, however, that the government was not required to provide services (including the provision of water) inside the reserve. The verdict was widely hailed as a victory for the indigenous inhabitants of the CKGR. Maintaining their ability to live in the reserve – as well as their public image – has proven to be a challenge, however. For a more detailed description of the case and its effects, see Saugestad 2011.

Following the 2006 verdict, some of the former residents of the CKGR began to move back to the reserve. The government was not required to provide them with services, including water. Reports soon surfaced, however, that the government was preventing residents from bringing water into the CKGR, or from drilling a new borehole at their own expense.

- Roy Sesana, head of First Peoples of the Kalahari and lead applicant in the CKGR court case, with lawyer Gordon Bennet. Credit : Survival International

In July 2010, the High Court of Botswana denied a bid by the CKGR residents to gain the right to access water on the reserve, with the argument that the Bushmen ‘have brought upon themselves any discomfort they may endure’. They appealed the case in September and on January 27 2011 the Botswana Court of Appeals ruled that they have the right to use their old well and to sink new ones, and that the government had been wrong to deny them this right previously. This case has made headlines (see for example New York Times) and has been reported extensively by Survival International.

The CKGR cases could have important impact and provides rich ground for analysis of the multi-layered aspects of indigenous rights. However this case affects a small percentage of San in Botswana. The majority are struggling to adapt to the necessities of participation in national society.

Culture

Langue, éducation et culture | - 11 avril 2011

Langue, éducation et culture | - 11 avril 2011

General

Botswana’s general approach to minorities, including the San, is assimilative. Botswana’s education and cultural policies are founded in the country’s strong anti-apartheid stance during its early decades of independence. Recognition of cultural and linguistic differences is still equated with the divisions of apartheid and with lack of access to mainstream institutions. Efforts to introduce minority languages in education or for other purposes have consistently been countered with the official argument that “we are all Batswana” and that it is against policy. The general position is that recognizing specific rights or needs of minorities will be divisive and unfair – either privileging or disadvantaging groups on ethnic grounds.

However, the government does recognize special needs based on circumstances, for example living in an area which is far from points of service provision. The Remote Area Development Programme (RADP), under the Ministry of Local Government, caters specifically for children from remote and impoverished communities (see also . There are no official figures illustrating the percentage of “Remote Area Dwellers” (RADs) who are San. However a common estimate is that more than 80 per cent of the RADS nationwide are San, and that this number approaches 100 per cent in some areas. The government of Botswana earmarks resources specifically to provide RAD children with the opportunity to attend government schools, including building and staffing hostels to accommodate children from remote areas.

Geographical / Statistics

Language

The dominant language in Botswana is Setswana, which is the national language and the predominant language of education for grades 1-3 (English is also used for these grades in some schools). English is the official language and in is the language of education for everyone after grade 4.

Around 20% of the population of Botswana speak a language other than Setswana or English at home. Some of these minority languages are Bantu languages (in the same family as Setswana) ; these include Ikalanga (11%) ; Seyeyi, Sekgalagadi, Thimbukushu and Otjiherero.

About 3% of the population speaks Khoe San languages at home. This language family is unrelated to the Bantu languages. San languages spoken in Botswana include Ju|’hoansi, Nharo, Khwedam, !Xoo, |Gui, ||Ghana, Tshua, Tsila, Khute, and ‡Hoa (see map).

Due to the structural and phonetic differences between Khoi-San and Bantu languages, San students are at a greater disadvantage then speakers of minority Bantu languages when they begin school. San languages are known for their click sounds and are phonetically among the most complex languages in the world. Some San languages have developed orthographies, including Nharo (using the Nguni system of representing clicks with the letters X, C, Q and Tc) and Ju/’hoansi and Khwedam (which both use the IPA symbols of || ! ‡ and | for the same basic clicks). Other languages are also being developed. None of these are currently used as languages of education .

Legislation / policy

The only languages developed for educational purposes in Botswana are Setswana and English, and the use of other languages is specifically prohibited by law. However, recently the government has indicated that it may be willing to develop other minority languages for educational use.

Legislation in Botswana places a strong emphasis on participation in the national institutions. The right of San / Basarwa to maintain their indigenous culture is considered contrary to national policy.

Corporal punishment is legal in Botswana in general, including in schools. Botswana rejected a recommendation by the UNHCR Working Group on UPR that corporal punishment be abolished in schools, citing it as a “legitimate form of punishment.” Corporal punishment is very often cited as a reason by San children for dropping out of school and is, by most accounts, contrary to the norms of San child-rearing practices.

Education, language and culture

There is no mother tongue education for speakers of languages other than English and Setswana. Teacher training is according to a standard model. One exception is the Bokamoso pre-school teacher training programme in D’kar, which incorporates San culture and language into its curriculum.

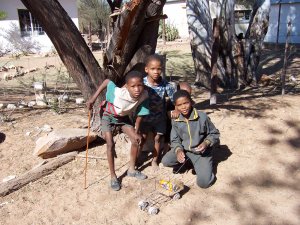

- San (Khwedam-speaking) children in First Grade at Xakau Government School, Botswana, photo : Jennifer Hays

Statistics on educational participation are not disaggregated by ethnic group so there are no official statistics on San participation in schools. However, it is generally accepted that San students have the lowest educational participation rate. In Botswana, a recent (2009) survey by the NGO Thuto Isago Trust found that, for example, in the freehold farms of Gantsi (Ghanzi) Farm Block – where most of

the farm workers are San – more than half the children between 6 and 15 were not in school.

Commonly cited reasons for the low level of San participation in government schools include the lack of mother tongue education, the use of corporal punishment, lack of school fees, or of appropriate clothes or other supplies, bullying, lack of respect for San culture, and the difficulty of living in a hostel.

Hostels : Because many San live in remote settlements or on farms, in order to attend school they must live in hostels. This is one of the most urgent educational issues for San communities. Children as young as 6 or 7 are taken from their homes and sent to live in dormitory hostels very far from their parents. In the past there was an explicit practice of sending children to hostels that were too far away for them to easily walk home ; although this is no longer specifically encouraged, there are reports of it still happening. Many of these children come from very small villages ; some children of farm workers even come from farms where they have grown up with only their immediate family. They are then taken to live in large hostels and attend schools with children from other groups whom they do not know. The hostel caretakers, teachers, and virtually all adults at the schools and hostels are from dominant ethnic groups and do not speak the language of the children. There is a well-documented frequency of abuse (including a very high occurrence of sexual abuse).

- Distribution of San languages in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, Source : Sidsel Saugestad and Kuela Kiema

Culture / subsistence

Most San in Botswana until fairly recently subsisted from hunting and gathering, and / or fishing. As the country because increasingly dependent on cattle farming, the San lost their land base. Today most are living in settlements. Hunting is illegal almost everywhere without a permit and traditional plant foods are depleted, especially in settled areas with higher population concentration.

Especially in the Ghanzi District, very many San are living as farm-workers. Farm work is generally very low-paid (or in some cases paid only through exchange for squatting rights and daily food and/or alcohol), insecure, and without benefits. Educational and medical services, as well as other services, are far and not easily accessible.

The production of crafts for sale to tourists or to other markets is a main source of income for many San in Botswana. The presentation of their culture for tourists, including bush walks and demonstrations of traditional dance ceremonies is also cultivated for the tourist market.

San artwork, notably from the Kuru Art Project, based in D’kar, has become popular in the international art world, and a handful of artists in the Ghanzi district earn large sums of money for their artwork. These earnings are generally redistributed among relatives and neighbors and the artists live in the same conditions as other community members.

There is little information on San / Basarwa in mainstream employment, as figures are not disaggregated by ethnic groups. Further study of employment patterns among San populations in Botswana would is needed.

Version imprimable

Version imprimable