Research Areas | India

Research project

Research project | - 27 July 2011

Research project | - 27 July 2011

For « Scheduled Tribes » peoples in India, the revendication of indigeneity and its specific rights depends eminently on the access to higher education, or to militant networks exceeding the regional state frame(executive), without speaking about the access to the UN. This possibility is attached to the ability to understand and to express himself in several dominant tongues (Hindi and English at least). The Indian Constitution has provisions to protect the minorities’ languages and cultures, as well as to provide primary education in maternal language for tribal children in the States with a strong tribal population (see VI). Unfortunately, such central provisions remain poorly implemented in the States in question (5fth Schedule), where the majority speaks other regional languages. Also, in the Constitution and in other more recent laws (see IV), the central government granted more theoretical autonomy to the Tribes than it appears in the regional realities. So, within SOGIP, we will focus particularly on three issues, concerning India, where the claims for local autonomy mobilize international statements :

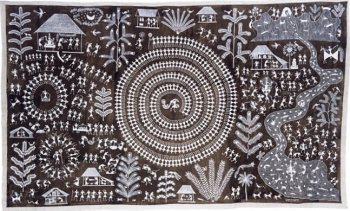

- Jivya Soma Mashe, acrylique et bouse de vache sur toile, 1999 / Thane District, Maharastra, Inde, Photo/Collection : Hervé Perdriolle

- http://jivya-soma-mashe.blogspot.com/ http://herve-perdriolle.blogspot.com/ http://indianartcollection.blogspot.com

1) access to education in maternal language and the development of an adivasi literature.

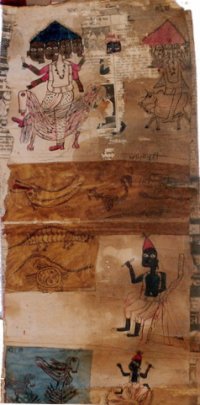

- Jadu Patua/Fête de Baha, anonyme, années 80, couleurs végétales sur papier, marouflé sur toile, 34x320cm, collection privée/Photo : Hervé Perdriolle

- http://herve-perdriolle.blogspot.com / http://indianartcollection.blogspot.com

In each such State, a Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Institute is in charge of writing teaching manuals, as well as to give a basic training in adivasi languages to the teachers of those areas. Beyond the common constat of education problems in tribal areas, we would like to study the actual initiatives in this field.

Amongst such initiatives, the experimentation of the Bhasha Centre (Gujarat), founded by Ganesh N. Devy (1996), specialist of literature and militant for the cultural rights of the adivasi, seems to be particularly promising In 1999, to this organisation was added a Tribal Academy in Tejgadh (in an area with a large adivasi population), offering (among other things) primary education in maternal language to adivasi children who droped out from mainstream schools. Due to his success, the Centre got official recognisance from the Sahitya Akademi (Indian Academy of arts) and then the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, as well as UNESCO. The previously quoted Institutes can now ask for the skills and resources of this centre. At another level, the Tribal Academy contribute to the emergence of an adivasi literature, whose authors claim now that ‘they do speak for themselves’.

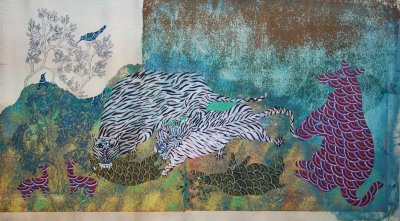

2) the education and literature topics is naturally linked with the issue of contemporary adivasi art and the intellectual property rights

Formerly collected for their ‘ethnographic’ value, adivasi paintings, for example, are more and more valorized on the national and international art market. While the Warli painter Jivya Soma Mashe recently received a national Award, numerous ‘traditional’ adivasi motives have been appropriated by urban turned ‘ethnic’ designers or artists. It is therefore necessary to explore the question of “exclusivity rights” on the “cultural expressions” (issue present for a long time in the field of Indian music : see Gradhiva 2010), as to how actual cases can be formulated ?

- Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962-2001), Tigers hunting, 1995 http://jangarh-singh-shyam.blogspot.com/ Narmada Valley, Madya Pradesh, Inde Photo/Collection : Hervé Perdriolle

- http://herve-perdriolle.blogspot.com/ http://indianartcollection.blogspot.com

3) the problems related to cultural and linguistic rights should not occult the more burning issues of land rights or rights to socio-political participation.

Without to work ourselves directly on those questions, widely debated today in India (PESA Act for example), we will follow the media and institutional debates on it. We will distinguish the different levels where such issues are actually articulated. We also focus on the self-representations of those groups, with a special attention to their link with land and earth (in myths of autochtony for example). One of the case study is the recent and very publicised Niamgiri hill one (Orissa), where a project of bauxite mining endangered the very existence of the Dongaria (“highlanders”) Kond tribal group. This case is particularly significant of one of the most sensitive aspects of the globalization for native peoples : the exploitation of the mining resources situated under their territories. The fight against the industrial undertaking of the underground so tends to become a commonplace of the contemporary ’indigenous situation’.

Data

General overview | - 27 July 2011

General overview | - 27 July 2011

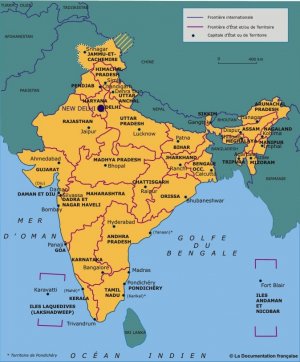

Topographical map of India

India covers an area of 3.3 million km2 and has a population of one billion people. Among them, about 8 % (84 millions) belong to the Scheduled Tribes constitutional category (see part III).

India is known for its castes system, or hereditary socio-profesional status groups, generally associated with Hindu values (purity, brahmanical rituals). The Scheduled Tribes, commonly called adivasi (in Sanskrit « original inhabitants »), have been defined by contrast with this system. Beyond their diversity, such groups share some common traits : an institutional division by lineages (more than by sub-caste), an highland habitat (by contrast with plains), minoritary languages (see VI), and some religious conceptions and practices distinguished from Hinduism as previously mentionned.

Indicators

- GDP per inhabitant : 1 020 $ in 2008

- Human Development Index (2005) : between 128 and 136th rank (on 177 countries).

- Poverty : according to the World Bank, in 2005, 42% Indians had less than 1,25 dollar per day in parity of purchasing power (controversial figures).

- Life expectancy : 63,5 years (2005)

- Health : sanitary question remains rarely politized, and the present economic growth does not imply necessarily the amelioration of the general Health situation.

- Literacy rate (2005) : 61 %

- The official rate of urbanization was 28% in 2001, but such data do not show the importance of peri-urban zones, the frequency of the very wide villages, and the strong density of population, even in rural areas. Since the middle of the 80s, the liberal politics try to invert the rural-urban ratio, implying the ‘sacrifice’ of the present agricultural world.

For other statistics and maps, see the Census of India website.

Political system

The Indian Union is a federation of 28 States and 7 Territories (among which the Andamanese and Nicobar Islands).

At the federal level, the President of the Indian democracy is elected by the members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) and Parliament (MP). The main power is exercised by the Prime Minister (PM, leader of the MP, who decide the ministers) and a Parliament, divided into a « Chamber of the States » (Rajya Sabha) and a « Chamber of the People » (Lok Sabha, whose members are elected according to the direct universal suffrage).

At the regional states level, the central agent is the Governor (appointed by the President and the PM). The members of the State Legislative Assembly (Vidhan Sabha) are elected every 5 years. The chief of the regional state is the Chief Minister (leader of the party who win the MLA elections), assisted by states ministries.

The central government is interdependant with the states’ ones. The competences are divided between both levels (police, santé, agriculture, among others, belong to the states), but the federal centre actually deal with the so-called ‘shared’ competences (social affairs, welfare, industry, etc.). Moreover, the states budget still largely depend upon federal funds.

The states’ boundaries follow most often linguistic divisions, but the latter cover sometimes other motivations. In the creation of the ‘tribal States’ of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh (2000), for example, the industrial ressources were clearly bigger stakes than the cultural revendications.

Since the New Economic Policy (1991), the neoliberal measures opened up the country to the foreign funds as well as to the World Bank plans (whose India is the first beneficiary). The laws of decentralisation transfered more power to the local collectivities (gram panchayat(1); block ; districts), but their autonomy remains limited (on the institutions particular to Scheduled Tribes, see IV).

Legal system

India knows a legal pluralism due to its history. The Constitution is still one of the the main source of Indian law, but celui-ci s’inspire aussi du système de jurisprudence british common law (acts & judgements). The juridical system is pyramidal, with the Supreme Court at its apex and the 21 High Courts, which competences often coextend with the territory of a State. Their judges are appointed by the President. The subordinated courts are subdivided into three instances. At last, numerous courts treat particular questions (land cases, forest, mines, etc.).

The private, civil right is divided into hindu and muslim rights. Some communities have also a customary law, directed by caste councils (panchayat) or village councils (among the adivasi for example, see IV).

Version imprimable

Version imprimable(1) For the administration, a gram panchayat is a «rural municipality» (which can contain many hamlets/villages), whose council is elected by all in the municipal elections. The council (panchayat), presided by a sarpanch, should be controled by the villagers’ assembly (gram sabha since 1992).

Regional context

Regional and global context | - 27 July 2011

Regional and global context | - 27 July 2011

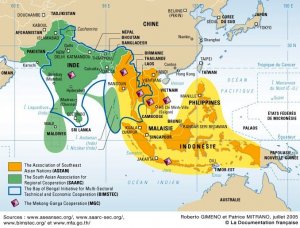

With a large territory and its central position, India is the main regional power in South Asia. The country is member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC, 1985, based in Kathmandou, Nepal), including today Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhoutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Maldives islands. The same countries signed a regional accord on Preferential Trade (SAPTA, 1995), and then of Free Trade (SAFTA, 2006).

India in the regional context

- Source : Roberto GIMENO et Patrice MITRANO, La Documentation Française ; Questions internationales n°15, sept.-oct. 2005

From the 1990s onward, in the context of the liberalisation reforms, India tended to come closer to the organisation of regional cooperation in South-East Asia (ASEAN, 1967). A free-trade accord between India and the ASEAN countries was signed in 2008.

India is a member of the des United Nations since the 30/10/1945. The country ratified the ILO Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (1957), and signed the U.N. Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007). India has also passed the Universal Periodical Exam in front of the Human Rights Commission in Geneva (UPE, 2008: South Asia / India).

International relations on the indigenous issues

The ‘indigeneity’ of the Scheduled Tribes became a sensible issue only after the adoption of the ILO Convention 169 (1989, not ratified by India), and above all the UNDRIP in 2007. As the latter Declaration does not define the characteristics of the indigenous peoples, the official position of India (like numerous countries of Asia and Africa) is that all Indians are indigenous vis-à-vis the colonisation.

Indigenous delegates from India started to participate in the Working Group on Indigenous Peoples (WGIP) meetings towards 1987 (1). The Indian Council of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (ICITP, affiliated with the World Council of IP, presided by Professor Ram Dayal Munda) is the first organisation who participated, as well as in the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII). Their main goal was to equate the Indian term adivasi/tribe with the new international one Indigenous People, in order to ask for the application of related international standards.

In the 90s, the newly created All India Coordinating Forum of Adivasi/Indigenous Peoples (AICFA/IP), a network of Indian organizations, tried to impose itself as an alternative to the ICITP. Since this period, various other adivasi & indigenous organisations were formed (2), to defend more localised interests (Naga for ‘Nagalim’ independence, Bodo for the separation of a ‘Bodoland’ from Assam) or specific ones (education or literature issues, women rights, protestation against mine or big dam projects – in Manipur for example –, etc.).

The main ones take also part of asiatic ‘umbrella’ organisations like : Asia Indigenous Peoples’ Pact (AIPP) ; Asian Indigenous & Tribal Peoples Network (AITPN).

Today, the debates on the indigeneity in India (academic (3) as institutional (4) ) have moved from real ‘first-ness’ on the territory towards the acknowledgement of a passed experience of dispossession, associated with the self-revendication of socio-cultural differences compare to the national dominant model, as well as a strong economic dependence and cultural attachment to land.

Version imprimable

Version imprimable(1) For a detailed chronology, an analysis of the controversies and respective positions, see Bengt G. Karlsson, « Anthropology and the ‘Indigenous Slot’. Claims to and Debates about ‘Indigenous Peoples’ Status in India »,Critique of Anthropology, SAGE Publications, 23 (4), 2003 : 403-423 ; « Asian Indigenousness : the case of India », Indigenous Affairs, 3-4, 2008 : 24-30.

(2) For a non-exhaustive liste, see the DOCIP website (Organisations/Country). For various reasons, the North-East tribal organisations prefer to be called « indigenous », and confine the name adivasi to tribal peoples of the rest of India. Then, both terms are juxtaposed in the common pan-indian organisations.

(3) For a balanced synthesis of the question, see V. Xaxa, Tribes as Indigenous People…. The issue still at stake is to know if the indigenous strategy is always useful, compare to the risk of ‘ethnicisation’ of the debates. See : Karlsson 2003 op. cit. ; Alpa Shah, « The Dark Side of Indigeneity? : Indigenous People, Rights and Development in India », History Compass, 5 (6), 2007 : 1806-1832.

(4) See the debate between James Anaya, the special Rapporteur on the Human Rights and fundamental freedom of Indigenous Peoples and the Government : 15th session, 14 Sept. 2010 (Addendum – Communications to & from Governments : A/HRC/15/37/Add.1, p.93-102).

Rights

Rights, law and Politics | - 27 July 2011

Rights, law and Politics | - 27 July 2011

Policy and regulations regarding Scheduled Tribes / adivasi

Proportion of tribal population by State

The Constitution of India gives a solely administrative definition of the Scheduled Tribes (1): ‘declared as such by the President of India’ (art. 342 ; 366-25).

The constitutionnal list of the Scheduled Tribes (462, see also : Census of India) integrated the colonial classifications of the tribes inhabiting Scheduled Areas (text of 1935 particularly). That is why some groups are classified as tribal in one state of the Union and not in an other. This list is also modified from time to time, as new groups can ask for integrating this category. Such request reach the President through the Departments of Backward Classes of the differents states (see below).

The Constitution has general measures of affirmative action for the benefit of adivasi :

- post reservation in the educational institutions (art.15.4-5) and in the administration (art.16.4 ; federal quota of 7,5 % of ST) ;

- seat reservation in the government bodies Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies (art. 330-335) ;

- measures regarding land and education (see V and VI) ;

- Welfare programs (art. 46, 275) ;

- creation of a National Commission for the Scheduled Tribes (NCST) (art. 338-338A). In principle, a powerful constitutional body, vested with the powers of a civil court (clause 8) for investigation & enquiry and recommandation.

The part X of the Constitution, dedicated to the Scheduled areas (art. 243) with a tribal population, divide their administration into two legislations :

The following central states : Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Orissa and Rajasthan (art. 244.1, and 5th Schedule)

Within those states, the Governor should :

- assist the adivasi to enjoy their rights (particularly to take care about the non-transfer of their lands, and to control moneylending practices) ;

- develop the Scheduled areas (economy, education, welfare).

- He is assisted by a Tribal Advisory Council, 20 members with 3/4 representing the ST at the state Legislative Assembly.

- A Minister of Tribal Welfare is created in the central states with a strong adivasi proportion (Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand : art.164.1).

- A Backward Classes Department manages aid programs, through a sub-Department/Institute of the Scheduled Classes & Tribes. The latter redistributes funds to the Development Agencies, and should care about primary education in adivasi language, on the proposition of each state (see VI). He is also to study and rule on the demands of integration for the ST list.

The north-east region (art. 244.2, 275.1A & 6th Schedule), i.e. the present states of Assam, Tripura, Meghalaya and Mizoram (art.371G) (2).

District Councils and Autonomous Regional Councils are created in the scheduled areas (3), with the power to legislate directly (with the approval of the governor) on :

- the land transfer and use, the forests and the regulation of slash and burn cultivation, the water resources, the village administration, the health, the succession of the chiefs, the marriages, divorces, succession and social customs.

The councils are also vested with the following power :

- of an appeal court on the tribal population under their juridiction ;

- to establish primary schools (in maternal language or not) ;

- to manage funds and to collect taxes ;

- to grant (and to negotiate) mineral prospection and extraction in their territory.

In October 1999, a central Ministry of Tribal Affaires (MTA) was created. Asked to coordinate the programs of development (among which " the primary responsibility " always rest on the other Central Ministries : Welfare, education, etc.), the activities of this ministry concentrate on the welfare, the scholarships to the students of the concerned groups, the information and recommandation about the implementation of legislations concerning tribal peoples : Forest Act ; Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 ; SC&ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. The MTA also manages the NCST, the promotion of tribal handicrafts (TRIFED) and tribal guests during the national Republic day celebrations (26 January).

In practice, these measures were not enough to mitigate the disparities (land dispossession, difficult access to education, the violence undergone especially on the scene by confrontations between special forces and Maoists or Bodo/Naga fighters, etc.). Regarding the institutions, the NCST has no financial, neither administrative autonomy, and the MTA activities have been criticized by the Parliamentary Standing Commitee on Social Justice & Empowerment. Its draft for a new ‘National Policy on Scheduled Tribes’ has been rejected as paternalist by several tribal / indigenous organisations (AITPN 2006 ; Karlsson 2004). They asked to leave the Welfare/development framework, aiming only to passive integration. Instead, they want a full recognition of their active right of self-determination and control over their lands & resources (‘Free Prior Informed Consent’ in case of displacement, compensation in lands and not in cash).

For the regions governed by the 5th Schedule, a significant step in this direction, is the Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, or PESA Act. Passed the 24 Dec. 1996 (based on the Bhuria Committee report, 1995), this act obliges the states to take into account the customary laws, the socio-religious practices and the traditional manners in the administration of the concerned municipalities.

Above all, this act extend the competences of the rural municipalities (village panchayat) in tribal areas (under the 5th Scheduled) in matters of justice, territory and resources. A key provision is the necessary consultation of the panchayat elected councils, as well as the whole « village assemblies » (gram sabha) for all development programs, acquisition of tribal land, management of territory and minor minerals and water resources.

The implementation of such an act nevertheless meets a lot of resistance in the regional States.

Other debates concern the customary laws and the relevance to keep/to restore traditional structures of power (village/district chiefs, in Jharkhand for example) within ’ the biggest democracy of the world ’.

Version imprimable

Version imprimable(1) In the Hindi version, the word adivasi is not used in the Constitution : Roy Burman 2009.

(2) The two latter states have been created by the North-Eastern Area (Reorganisation) Act, 1971, as for Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. Nagaland (created in 1962), Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh have special statuses , governed by the articles 371 A, C and H of the Constitution. Sikkim (1975) is under the article 371F.

(3) One can note, in Assam, the extension of the powers granted to the Autonomous Councils of North Cachar Hills and Karbi Anglong, as well as to the Territorial Council of Bodoland, by special amendments in 1995 and 2003.

Territory

Land, territory and resources | - 27 July 2011

Land, territory and resources | - 27 July 2011

The history of the Indian land system is very complex, on the scale of that of the country. Individual tenures coexisted with village community tenures, managed by the chief (secular/ religious). Among the adivasi, the more common village division separates the founding lineage, representing the « peoples of the earth » (Bhumiya, Bhuinhar), from the later inhabitants, depending on the first ones for the usage of local lands. In a widened sense, that status and title was ritually recognized in some kingdoms. Apart from the more recent adivasi term, it represents the indigenous basis for the modern distinction between « autochtonous » and secondary populations.

Today, in non-forested area, the majority of the villages have land registrations, and the owners, private propriety titles (patta). This is the case in the plain areas, but numerous tribal peoples are living on forested highlands, where the land belongs to the Ministry of Environnement & Forests (see below).

The Constitution

The constitution prohibits the transfer of lands belonging to S.T. towards non-tribals (art. 244.1). In practice, there is often some means to bypass the law (to buy in the name of an isolated and manipulated tribal person), more over in the areas where the adivasi are less educated and under the power of moneylenders. But the individual transfers of cultivation land are still few things compre to the alienation of tribal lands by the states themselves (1). The 44th Constitution amendment (1978) removed the propriety right from the list of the fundamental rights, while the article 300-A introduced a State right for the requisition of lands (eminent domain).

Dams

The adivasi (8% of the total population) represent 40 to 50 % of the peoples displaced by dams since the independence of India. The most famous example is the Sardar Sarovar one, on the Narmada river, where two thirds of the displaced persons (240 000) belong to Scheduled Tribes (2). The embankment of waters entails, not only the displacement, but also a limitation of the access to the water for the populations, whereas the schemas of compensation are manifestly insufficient.

Forests

In 2003, 23% of the national territory recovered from the MoEF. The administration of forests inherited at first from the colonial management, judging the inhabitants-users of forests as illegal intruders. Also, the picking and the essartage which they practised were perceived as economically irrational and striking a blow at the integrity of the wooden and vegetal resources. The collection of Minor Forest Products was however recognized, then the rights and the knowledges of the countryman populations through a Joint Forest Management program (1990).

Passed in 2006, the Scheduled Tribes & Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Rules bypass, recognize family and collective land rights in forest areas for S. Tribes and other forest dwellers living from the forest (3)

But, this law remains largely unimplemented, and tribal are still arrested by forest guards (especially in national parks). The responsability for recognition and vesting of those rights still rests with the States governments. Then, the village assembly or Gram Sabha should establish the requests and deposit them to the Forest Office, so that the law remains little implemented. The dense forest largely disappear in India, but essentially for the benefit of industrial, in particular mining projects.

- Farmer working in his rice field in front of Lanjigarh refinery, Kalahandi dist., Orissa (December 2010). Photo: Raphael Rousseleau

Mines

Numerous mineral ressources are situated precisely on the highlands or in restricted highland or montaneous areas, inhabited by Scheduled Tribes. The industrial legislations (Extractive Industries Review, 2004) have integrated the necessity of the Free Prior Informed Consent. Public hearings are then organised, but remain under close scrutiny and intimidations by companies.

In 2007, in the Samata Judgment (Samata NGO vs State of Andhra Pradesh), the Supreme Court reasserted the tribal people’s constitutional and fundamental right to the inalienability of their land (cf. 5th Sch.) and insisted that only tribal-owned or public sector companies could acquire tribal land for project. That sentence henceforth sets a precedent, but the international private companies found the means to subvert the constitutional guarantees: they sign agreements of cooperation with state-owned mining companies (Public Sector Undertakings) to operate in joint venture (4).

In 2008, The Government published the orientations of its National Mineral Policy (see Policy & legislation), asserting the primacy of the mining industries for the economic development of the country. The unique protective measure imposed to the companies is to integrate their projet in the Sustainable Development Framework, and to garantee the Companies Social Responsability. But, the control of such regulation goes to private auditors, possibly open to corruption. Be that as it may, far from the shining publicity on development, the majority of the districts producting minerals are among the poorest in India.

At last, besides the forests, the mining industries touches the water ressources as well, as very numerous dams are built to fill the needs in energy of that sector. Once more, the exploitation of the eastern montaineous areas would dramatically disrupt the cycle of the water, and the alimentation of the plain cities below (5).

Version imprimable

Version imprimable(1) Nandini Sundar (ed.), Legal grounds. Natural Resources, Identity and the Law in Jharkhand, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2009.

(2) Amita Baviskar, In the Belly of the River : Tribal Conflicts over Develoment in the Narmada Valley, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1995.

(3) Those Other Traditional Forest Dwellers should justify three conditions : -to have primarily resided in the forest for 75 years prior to the 13Dec2005 ; -to be, at present, dependent on the forest or forest land for bona fide livelihood needs ; -to have been in occupation of the forest land before the 13Dec 2005.

(4) Felix Padel & Samarendra Das,Out of this Earth. East India Adivasis and the Aluminium Cartel, New Delhi, Orient Blackswan, 2010 (p.116, 191, among others).

(5) See : Padel & Das op cit., Health of the Hills is the wealth of the plains on Samata, as well as Mines, Minerals and Peoples websites.

Culture

Language, education and culture | - 27 July 2011

Language, education and culture | - 27 July 2011

Languages

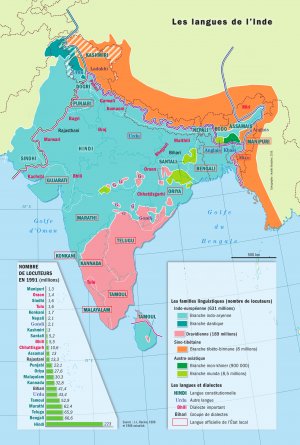

India has two major linguistic families

(data : Census of India 2001) :

A) the ‘indo-aryan’ languages (a branch of the Indo-european languages) in the north (Hindi : 41% of the population, Bengali : 8,1%, etc.) ;

B) the dravidian languages in the south (Telugu : 7,2%, Tamil : 5,9%, etc.).

The minor languages are distributed among :

C) the tibeto-burmese languages, in the himalayan regions (Manipuri : 1,4 million of speakers, or 0,14%, Bodo : 0,13%, etc.) ;

D) the austro-asiatic languages, disseminated over the eastern and central part of the country (Santali : 6,4 million of speakers, or 0,63%, Oraon, etc.) ;

E) the andamanese languages (Jarawa, Onge, etc.).

Official languages of the Union : Hindi, English («official associate language»). Present constitutional languages (14 in 1950, 23 today, here by families) :

A) Assamese, Bengali, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kashmiri, Maithili, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Ourdou, Panjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi ;

B) Kannada, Konkani, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu ;

C) Manipuri (since 1994) ;

D) Santali (since 2003).

- Map entitled "Les langues en Inde" (languages of India), first published in "Dictionnaire de l’Inde contemporaine" (Dictionnary of contemporary India), © Armand Colin, 2010 / Cartographer : Aurélie Boissière (map reproduced with the authorization of publisher Armand Colin)

Education, literature

- Ganesh Devy (at the back) among his adivasi pupils of primary school, «tribal Academy» of Tejgadh, Gujarat (december 2010). Photo : Raphaël Rousseleau

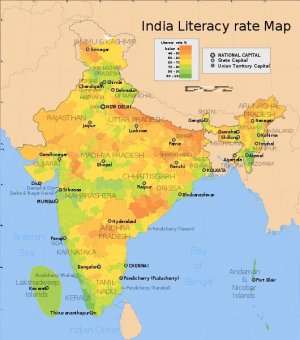

The Constitution claims the principle of universality of education, but became a fundamental right (up to 14 years old) in 2002. Since 1976, the States (ministries of education) share the educational competence with the federal Centre (National Council on Educational Research and Training). The funds (Collections) allocated to education remain unfortunately less than 5 % of the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), and the primary education still largely depends upon social origins. The public schools (marked by a strong rate of absenteeism of teachers) is frequented only by the childrens from discriminated families, while the privileged families prefer English private schools. The southern part of the country made big progress, and the North-East took the opportunity of the English speaking christian schools, but the literacy rate remains low in the central and eastern states of the country, as well as Rajasthan, all states with large adivasi populations.

Literacy rate

- Source : Census of India 2001 ; Survey of India map.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:India_literacy_rate_map_en.svg

See also the very useful maps of websitedemographie.net.

According to the Constitution, any cultural or linguistic minority has the right to conserve its language and culture (as well as its script) ; to establish educational institutions of its choice (art. 29.2, 30). Still according to the Constitution, each state should offer facilities for instruction through the mother tongue at the primary stage of education (art. 347, 350a) (1). The Ministry of Tribal Affairs develops some measures on superior education also. In 2007, the Parliament has voted the creation of a Indira Gandhi National Tribal University (IGNTU) to be situated in Amarkantak (Madhya Pradesh).

As a matter of fact, the implementation of such federal regulations remains in the hands of the states (creation of a special department, publication of manuals, training of th teachers). Created on linguistic basis, the regional states promote their dominant language above all, and tend to let to the tribal communities themselves the transmission of their language and culture (2). So, apart from the indigenous of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands – whose culture is on the eve of extinction –, the more discriminated groups are the adivasi of central India, under the 5th Scheduled, as they are generally less educated and more submitted to regional politics.

For such de facto reasons, despite of the constitutional provisions, V. Xaxa speaks about a silent assimilation of the tribals in central India, compare to the socio-political integration working in the North-East thanks to the larger self-determination of the populations under the 6th Scheduled (3).

Building on post-colonialist theories, some adivasi militants invest the literary domain, in the following tribal larger languages : in the East the Santali and, in the West the Bhilli and related languages (4). Apart from a Mundari department in the University of Ranchi (Jharkhand), there is a All India Tribal Literary Forum and a Adivasi Academy, Tejgadh, in Gujarat, helping the publication of books and newspapers in tribal languages.

Religion

Religious freedom is protected by the Constitution, as well. Already present in the colonial census, the « tribal religion/origin » category disappeared from offical classifications shortly after the independence (Xaxa 2005). For this reason, most of the tribal peoples are registered as Hindus, except in the more politicized areas like in Jharkhand (see the Census of India), where one can find the stronger registration of « other religion », other than the official ones (Hinduism, Christianism, Islam, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikh religion). The 1st January 2011 (in Burnpur, Bengal), 750 delegates from organisations united in an Adivasi Conference, asked for the restauration of a distinct category for their religion. The exact name remains nonetheless disputed (Adi dharma / Sarna dharma…).

In some areas, Hindu extremists put strong pressure on the adivasi (whom they prefer to call vanavasi : « forest dwellers », implicitly reducting them to ‘primitive peoples’ subjugated by the mythical ‘Aryans’) in order to make them adopt their own ‘purified’ brahmanical Hinduism, or even enrol them in their anti-christian or anti-muslim movments (5). Such extremist do not tolerate that the adivasi, natives of India by definition, can claim a religious identity to much different from the Hindu one.

Version imprimable

Version imprimable(1) For a synthesis on the linguistic constitutional provisions in India, see the University of Laval website.

(2) Virginius Xaxa, « Politics of language, Religion and Identity: Tribes in India », Economic and Political Weekly, March 26, 2005, pp. 1362-1370.

(3) This larger autonomy echoes the Verrier Elwin’s principle (already taken over in the Nehru’s panchasila) concerning the present Arunachal Pradesh (former North-East Frontier Agency) to let the tribes ‘follow their own lines of development faithfull to their own genius’.

(4) On the formers, see Marine Carrin’s works, on the latters, see the Bhasha centre publications linked with the Adivasi Academy, Tejgadh (Gujarat).

(5) See the publications by Peggy Froer, Amita Baviskar and Alpa Shah.