Research Areas | Australia

Research project

Research project | - 14 June 2011

Research project | - 14 June 2011

Organizing self-determination

Indigenous peoples’ right to self determination is the fundamental principle enshrined in article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In Australia, the concept of self-determination is associated with the policy bearing its name established by the Whitlam government in 1972. During the 1990s, the policy was hotly contested for having failed to deliver the expected outcomes in terms of ameliorating the living conditions of most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. After a decade of “practical reconciliation” whereby public service delivery became conditional, the Rudd and Gillard governments have committed themselves to “reset” the relationship between indigenous peoples and the Australian government. The official apology in 2008, the endorsement of the UNDRIP the following year, and the Closing the Gap policy purport to demonstrate this commitment.

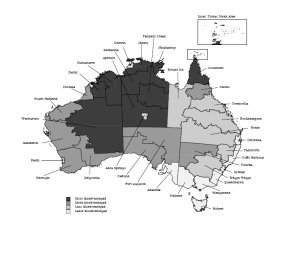

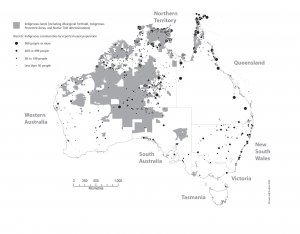

- A graphic representation of the diversity of Australia’s First peoples and cultures and their networked organisation. Created by M. Préaud

One of the main effects of the self-determination policy was the development of several thousand indigenous organizations throughout Australia. Although greatly diverse in function and objectives, these organizations are the principle vehicle for the political representation and participation for Indigenous peoples. They also provide the main space of articulation between the different institutions participating in the

Indigenous field:

- Classical indigenous institutions: kinship and exchange systems, rituals, socio-territorial organization;

- (post) colonial indigenous institutions: communities, service organizations, local, regional and national representative organizations;

- State institutions: governments, agencies, administrations;

- International institutions and third parties: UN agencies and special rapporteurs, transnational companies, funding organizations, NGOs;

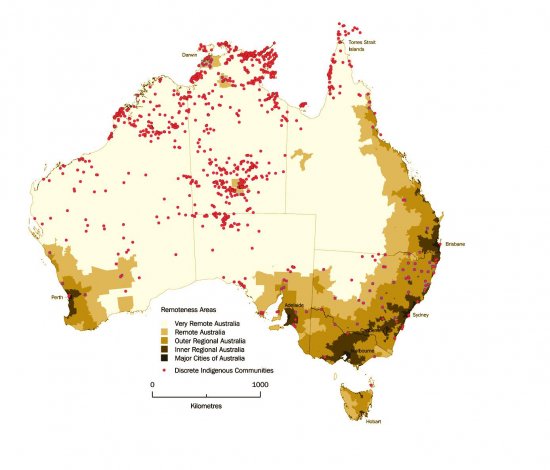

- (in development) Proportion of Indigenous Peoples in the total population against disadvantage quartiles. Source : Atman & Hughes 2010

Indigenous organizations are the core of this research project as they are sites of articulation between different scales of practice and governance, and also places in and through which norms, discourses and representations are circulating. The main purpose of the research is to describe these circulations in order to illuminate the pragmatic conditions for the realization of the principle of self-determination.

Indigenous models of development

The fact that 20% of the Australian land mass is now considered indigenous land (under a variety of statutes giving rise to different rights and interests) is an important outcome in terms of rights and the potential recuperation of an autonomous economic base. In the last decade, numerous programs of natural and cultural resource management (such as ranger teams looking after country, Indigenous protected areas, and others) were developed at the local level by indigenous groups. These programs are an important site for the development of what has been termed a “hybrid economy” where the indigenous subsistence sector is articulated to the market and state sectors (Altman 2001). These programs allow the emergence of new forms of governance integrating indigenous authorities grounded in the ritual domain. These programs, which have developed into regional and national networks harnessing global environmental concerns, have the potential to transform the economic and political landscape of contemporary Australia through a “two-way” environmental management. To what extent would they alleviate the tensions between equality of opportunity and the sustenance of indigenous cultural singularities?

See map above.

By examining the legal, anthropological and historical determinations that constrain the recognition of indigenous territorialities, the research will question the conditions of possibility and the contours of landed indigenous autonomies. The research will illuminate the cultural and historical dimensions giving rise to and nurturing indigenous models of “good living” while also integrating the partnerships, collaborations and articulations that make such models possible in the Australian and global contexts.

- Kantri Laif is a newsletter about Indigenous-led natural resources management programs across Northern Australia. It is edited by NAILSMA, an organization federating Indigenous Land Councils across these regions.

Indigenous subjectivities and the normative framework

- Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia was edited by ANU researchers Jon Altman and Melinda Hinkson in response to the vote of the NTER, offering a critical analysis of its context, structure and potential effects.

By definition, indigenous peoples are defined, and define themselves, as different from (or even in opposition to) non-indigenous peoples. In Australia, this question has a real historical, legal and institutional depth which constrains the way Aboriginal and Torres strait Islander people formulate their claims, identities and aspirations. Moreover, the representations and imaginaries associated with the first peoples of Australia – the oldest known continuing culture, but constantly threatened in its authenticity – weighs heavily on the politics of difference and political and academic discourses. The Northern Territory Emergency Response (2007) is a clear demonstration of the actuality and acuteness of these issues.

What can be the impact of the official support for the UNDRIP? How to understand the Australian government’s change of attitude since its initial negative vote? By analyzing the institutional responses and comparing them with data collected during fieldwork , the research shall provide answers to these questions through:

- A critical analysis of the appropriation and implementation of UNDRIP in Australia;

- A critical examination of the postcolonial status of the country and a consideration of the conditions of possibility for an effective decolonization of the continent.

Version imprimable

Version imprimableDISCLAIMER : Throughout these pages, for convenience I alternately use the terms Indigenous or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to designate Australia’s first peoples. The diversity of Indigenous Australian people is reflected in the many names they give themselves, according to language, social or territorial organization or historical circumstances. SOGIP and its members recognize and value the cultural and historical diversity of Australia’s First Peoples, and recognize that certain generic terms have been used for discriminatory policies and practices. Wherever possible I use the name that people use for themselves.

Data

General overview | - 14 June 2011

General overview | - 14 June 2011

SOURCES : Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Social Survey 2008,, HREOC 2008, National censing 2006

Demography

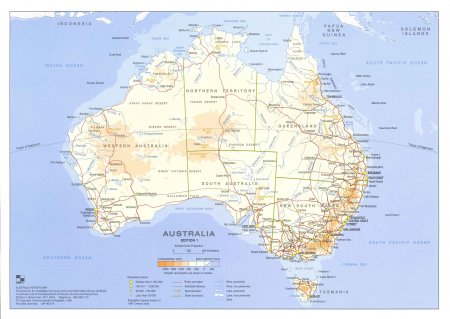

Australia is a sparsely populated country, with a surface area of 7 682 300 km2 and an average density of 2,5 people per square km. Given the size of the country, these figures obscure the high diversity of situations that exists between densely populated urban areas, and vast continental regions that would be deserted but for the presence of indigenous peoples.

Indigenous demography

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) people numbered about 517 000 in 2010, or about 2,5% of the total population (22 million). Among the indigenous population, 90% identifies as Aboriginal, 6% as Torres Strait Islanders and 4% as descended from both.

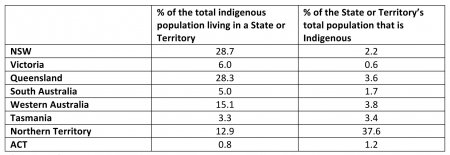

Table 1: Location of Indigenous peoples - by State and Territory (2006)

With a median age of 21 (compared to 37 for the non-indigenous population) the indigenous population is young and is growing more rapidly than the rest of the population. Between the 2001 and 2006 census, their numbers have increased by 13%.

The distibution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people matches that of the general Australian population: 75% indigenous people live in urban, inner and outer regional areas, while 25% live in rural and remote areas, a much higher percentage than that of the non-indigenous population.

Political and Juridical Regime

Australia is a parliamentary monarchy with a federal division of powers enshrined in the 1901 Constitution. The Sovereign of England is the official head of state and is represented by the Governor General. Executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister (leader of the majority in Parliament) who is responsible to the Parliament (Senate and House of Representatives).

Australia is divided into six States and three self-governing Territories:

New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Territory of Norfolk Island. Each state has its own bicameral Parliament, except Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory which have one chamber of Parliament. Unlike the states, whose powers are defined through the Constitution, the powers of the territories are defined in Australian Government law which grants them the right of self-government (which also means that the Australian Government can alter or revoke these powers at will).

The House of Representatives is elected for three years. It is responsible for matters of diplomacy, foreign trade, taxation and defense, among other responsibilities. The State and Territory Parliaments have extended responsibilities in matters of civil right and responsibilities which include: education, transports, environment, energy, health, police, agriculture and criminal law. Each State or Territory has its own judicial hierarchy from the local level (magistrate court) to the High Court.

The division of powers between the Commonwealth and the States is the subject of ongoing debates, with the particular importance of tax redistribution. The federal High Court, which is the highest jurisdiction of the country since 1986, deals with these conflicts and is the supreme court of appeal.

The third level of government is local and includes cities, urban areas and shires.

Some Socio-economic figures on Indigenous Peoples of Australia :

NB : These are general figures that do not reflect the great diversity of Indigenous situations in Australia. Data collection and interpretation is problematic. According to the 2006 census, 50% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were in the national average.

- Indicator of Human Development :

Australia = 0,970 (2/186 countries)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples = 103/186 (estimate)

- Life expectancy : on average 10 years less for ATSI people than for the rest of the population (ABS 2009). In the Special Rapporteur reports, the figure is 17 years less than average.

- Health : Health reports, census data and other studies indicate the persistence of a significant gap in health and access to health services between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. The gap can be observed in the prevalence of chronic diseases (e.g. type 2 diabetes, cancers, circulatory diseases) and STDs (including HIV), and in a rate of infant mortality three times of that of the non indigenous population (HREOC 2008).

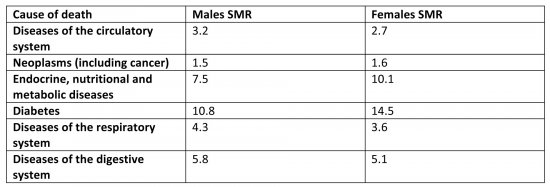

Table 2: Indigenous Deaths, main causes, 2001-05 - Standardised

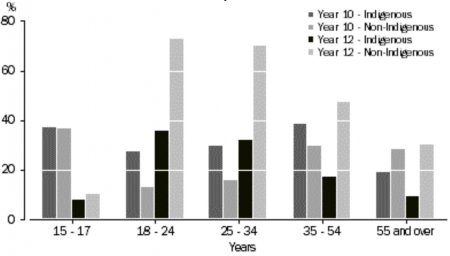

- Education : : 21% of indigenous students achieve secondary education (year 12), compared to 53,8% of non-indigenous students who do.

Table 3: Highest year of school completed by age group (2006)

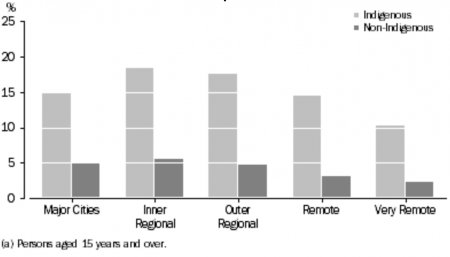

- Employment : 16% of active Indigenous Peoples are unemployed (compared to 5% for non-Inidgenous people)

Table 4: Unemployment rates(a) by remoteness areas (2006)

- Incarceration rate : 2Indigenous people represented 24% of the prison population in 2008.

- Juvenile detention : 44°/00 of indigenous youth are under justice supervision or detention against 3°/00 for non-indigenous youth.

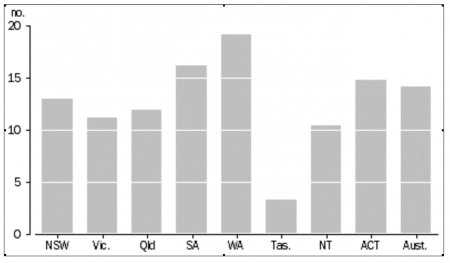

Table5 Ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous age standardised imprisonment rates, by state and territory (2006)

Regional context

Regional and global context | - 14 June 2011

Regional and global context | - 14 June 2011

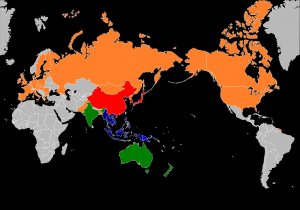

Australia’s international relations

International institutions

Australia is a founding member of the United Nations Organization and has participated in the redaction of the UN Charter. It is party to most of the Human Rights treaties and conventions. In 2009 the federal government announced official support for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. On 27 January 2011, Australia passed its Universal Periodical Review at the Human Rights Council in Geneva (online reports).

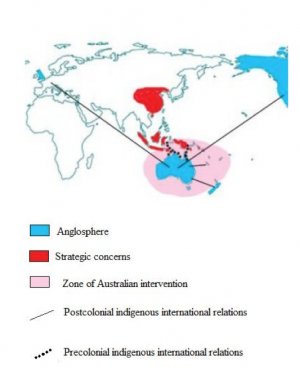

Regional Context

After the Second World War and the decolonization of the British Empire, Australia has sought to inscribe itself more firmly in the Asia-Pacific context. This was done through international cooperation, aid programs and military operations.

Australia is a member of the APEC, an economic organization to which States on the Pacific rim are party to. It is also a partner of ASEAN, a south-east Asian organization of political and economic cooperation. It has become a party to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation of the ASEAN in 2005 and has signed with ita program for advanced partnership in 2007. Australia participates to the South-East Asian Summit since its inception in 2005. Australian strategic interests include commercial exchange as well as security against perceived terrorist threat originating in Indonesia.

Australia is also a member of the Pacific Island Forum created in Wellington in 1971. It is with New Zealand the main funding state of the organization. With New Zealand, Australia actively promotes a free-trade agreement with the South Pacific states (PACER-Plus).

During the 1990s, and even more so after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Bali bombings of 2002, Australia has redefined its role in the region in light of its bilateral relations with the USA and their “war on terror”. It is not only an aid donor but also a military power that intervenes in what it considers as a Melanesian “arc of instability” to maintain peace and prevent terrorist actions (Bougainville 1998, Solomon Island 2003, Timor Leste 2006). Australia also maintains close political and economic relationships with its former colony of Papua New Guinea.

Indigenous international relations

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have long entertained cultural, political and trade international relationships, especially with Papua New Guinea and Makassar (Celebes Island, Indonesia). At the beginning of the 20th century, Marcus Garvey’s ideas of black internationalism and liberation reached Australia where they were appropriated by Aboriginal activists. Later in the century, the Black Panther and civil rights movement also has a strong influence on Australian developments (Maynard 2007).

With the setting of national representative organizations in the 1970s, Indigenous people where able to participate in the formation and development of the global indigenous movement. Represnetatives from Australia attended the first meeting of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples in 1977. Since then, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have actively participated to the indigenous institutions at the United Nations. People like Tom Calma, Mick Dodson and Les Malezer have played an important role. In 2009, the aboriginal lawyer Megan Davis was appointed to the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York.

After the abolition of ATSIC in 2005, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, an organization developed through the Australian Human Rights Commission, is the first formal attempt at restoring a federal indigenous representative organization. The first elections to the Congress are due to take place in 2011. The Indigenous Peoples Organizations informal network is also pursuing a work of lobbying and representation.

There is no formal regional indigenous organization in the Pacific or in the Asia-Pacific region. Some forums such as the Festival of Pacific Arts are important meeting place for indigenous peoples across the region. At the UN and other global institutions, the Caucus of Pacific Indigenous Peoples has played an important role as a meeting and networking place and continues to play and active role in global indigenous forums. Further, a growing number of individuals – academics, activists, organization chairpersons, etc. – maintain relationships with other indigenous peoples across the world, particularly in the Anglosphere. These relationships are an important source for the development of new ideas and the renewal of indigenous political discourse in Australia.

Rights

Rights, law and Politics | - 14 June 2011

Rights, law and Politics | - 14 June 2011

Indigenous integration to Australian citizenship

In September 2010 Ken Wyatt became the first aboriginal person to be elected at the federal House of Representatives. Before him, only the Senate had hosted Aboriginal senators Neville Bonner and Aden Ridgeway. Also in 2010 the first aboriginal political party was officially registered. Because they have become a minority population through the colonial process, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people confront tremendous difficulties claiming their rights and making their interests heard within Australia’s democratic institutions. Although there may be more indigenous people elected at the State and Territory level, they remain a minority and constrained by party discipline.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have progressively acquired citizenship rights and entitlements from the 1960s onwards. Until the 1967 constitutional referendum, they were not included in the national census and the Commonwealth government could not make specific laws for them. However, Indigenous socioeconomic disadvantage remains a barrier to their effective political participation.

Policies

In terms of Indigenous rights, the move to a policy of “self-determination” in 1972 by the newly elected Gough Whitlam’s labor government represented a fundamental shift. With the possibility for the federal government to legislate on indigenous affairs, former distinct political and administrative regimes of control and assimilation were abandoned.

These policies had been established by the colonies, and later by the states of the Australian federation, first in a perspective of “protection” (1850-1950) then in one of “assimilation (1950-1972). In the different States and Territories, indigenous people were removed from their lands and regrouped within a range of institutions – prisons, missions, reserves, hospitals, orphanages and pastoral stations.

These policies were inspired by eugenics and social Darwinism. They established distinctive treatments of indigenous people according to their blood quantum: while “full-bloods” were to be left to disappear, children and people of mixed descent were to be absorbed, both biologically and culturally within the dominant population. Between the end of the 19th century and 1972, these policies authorized the removal of thousands of children from their indigenous parents to be “educated” within white institutions in the denial of their origins. In 2008, the Prime Minister Kevin Rudd presented an official apology to these “Stolen Generations".

Indigenous Rights in Australia

In the 1970s, thanks to the work of Aboriginal-led activists groups and the Whitlam government, the legal and administrative framework of indigenous self-determination was established. It has since been regularly revised, contested and amended. Some fundamental elements do remain:

- The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) which implements the UN Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination;

- The Aboriginal Communities and Associations Act 1976 (Cth) allowed for the creation of self-managed communities directed by elected councils, and of a great number of indigenous organizations (legal services, health services, cultural, political and other organizations, peak bodies). These organization are the most important form of indigenous representation and political participation;

- The Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 (NT) was the first legislation that allowed land claims based on traditional connection that the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) will amend and extend to the whole of Australia (mostly on vacant crown land);

- National representative bodies: National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (1973-1976), National Aboriginal Conference (1978-1986), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1989-2005). The newly established National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples seeks to follow on these organizations while having a wholly different structure and inscription into the Australian institutions; These organizations have been at the forefront of campaigns for a Treaty between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians

- The Aboriginal social Justice Commissioner position was created within the Australian Human Rights Commission in the wake of the 1991 report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Death in Custody. Every year his Native Title and Social Justice reports are tabled in Parliament.

Indigenous politics

The politics of indigeneity is characterized in Australia by a structural tension between the aspiration to equality and the maintenance of cultural difference (see for instance Stokes 2002, Kowal 2010).

The self-determination policy allowed the formation of an indigenous bureaucracy and of indigenous administrative authorities who work in parallel, sometimes in conflict, with traditional authorities and activist groups. Indigenous classical systems of distributed and localized authority remain highly problematic to a political and administrative structure which is at once centralizing and fragmented. Indigenous organizations are intercultural spaces of negotiation between these different strands of authority as well as with the State. However, increased financial and administrative control procedures limit the capacity of these organizations to accommodate these different regimes.

The field of indigenous affairs, or what Rowse defines as “the indigenous sector” is plural and not aligned on a strict indigenous/non-indigenous division; there are many visions of what constitute desirable or sustainable development. Different models of Indigenous development are proposed, ranging from economic integration, the promotion of education, land rights, constitutional recognition of first peoples status to the implementation of indigenous collective rights as enshrined in the UNDRIP.

International scrutiny

The mechanisms for the implementation of indigenous people’s human rights in Australia remain fragile in the absence of any constitutional protection of human rights. Three states have recognized indigenous people in their constitution – New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria – but not their rights. The Government has appointed a panel of experts to prepare a referendum on the constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for 2013.

Historically, Australia has been an active supporter of human rights at the international level. Its attitude within its domestic domain has been more ambiguous. Under the liberal government of John Howard (1996-2007), the self-determination policy has been severely criticized for actually worsening the situation of indigenous people and replaced by a policy of “practical reconciliation”. Legislation translating this move has been condemned by human rights treaty bodies and has caused intense debate in Australia. Two of the more critical issues are the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) and the 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response which have necessitated the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cwth). In January 2011, Australia underwent its first Universal Periodical Review at the Human Rights Council in Geneva (treaty bodies report here). The scrutiny of international institutions is all the more attentive because Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have participated in United Nations indigenous forums since their inception.

Territory

Land, territory and resources | - 14 June 2011

Land, territory and resources | - 14 June 2011

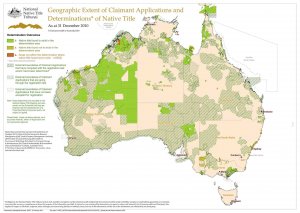

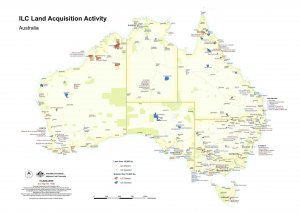

In 2010, approximately 20% of the Australian landmass is recognized as Aboriginal lands under a variety of titles, regimes and statutes giving rise to different rights and interests. Most of these lands are in the Northern and Central regions of Australia, where the proportion of indigenous people in the population is highest and where urbanization is limited. After two years of settlement predicated on the doctrine of terra nullius, the proportion of indigenous lands can be read as a sign of the reconciliation process.

Conquest & settlement

The Crown progressively acquired political and territorial sovereignty over the Australian continent from 1770 onwards. At the constitution of the Australian federation in 1901, this sovereignty was vested in the Commonwealth of Australia. This unilateral acquisition was legitimated a posteriori in the Australian courts by virtue of the international law doctrine of res or terra nullius and the common law doctrine of desert and uncultivated lands.

The Crown acquisition of territorial sovereignty de facto superseded indigenous peoples’ land rights and outlawed their presence on the continent and their assertion of their laws, countries and rights. The legal maneuver allowed for the dispossession of indigenous people, their displacement and institutionalization, and the bloody repression of their resistance to settlement.

Recognitions

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have always struggled against colonial dispossession but it is only in the second half of the 20th century that their claims started to be effectively heard and their land rights recognized.

The bark petitions sent to the Parliament in 1963 (text here) by Yolngu clan leaders against the establishment of a bauxite mine on their country is one of the first public expression of land rights struggle and the demand for the recognition of aboriginal land title. Blackburn J effectively recognized the existence and solidity of aboriginal laws. He ruled, however, that these did not give rise to proper proprietary interests in land. This judgment (Millirpum v Nabalco) led to the Woodward Commission which resulted in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976, the first legislation allowing indigenous people to claim lands based on traditional occupation and connection.

In 1992, the High Court delivered the Mabo 2 judgment which, after 10 years of procedure, established that the Australian common law could recognize native title to land. Although the judgment was made about the island of Mer/Meriam in the Torres Strait, Edward Koiki Mabo’s country, the judgment had consequences for the whole mainland as well. The Native Title Act (Cth) 1993 extends the claim process to all indigenous groups able to demonstrate occupation, connection, the existence of laws and customs ruling land interests and their maintenance.

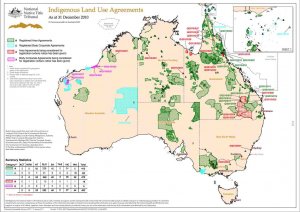

The Mabo judgment came as a shock to non-indigenous Australia. It created intense debates and was actively critiqued by mining lobbies, pastoralists, conservative politicians who feared that their access to resources might be threatened or wrongly argued that individual land titles might be revoked. The 1998 Native Title Amendments passed under the Howard government sought to give “certainty” to title holders. The Amendments have been regularly condemned by Human Rights institutions (especially the Committee for the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination) because, among other elements, they assert the inferiority of native title to any other title to land, and increase the complexity of procedure and the burden of proof for indigenous claimants.

Limits

In its current form, the Native Title Act seems severely limited: it excludes a large number of people from the procedure, compensatory land acquisition has been limited, the procedure has created many internal divisions and conflicts, the poor resourcing of Native Title Representative Bodies despite the length of procedures and the heavy burden of proof, etc. The regular condemnations and recommendations by international institutions illustrate these limits. These include: the Human Rights Council, CERD, CSCER, Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights and Fundamental Freedom of Indigenous Peoples.

Further, the Native Title procedure exhibits aspects of what anthropologist D. B. Rose has described as “deep colonialism”: “conquest embedded within institutions and practices which are aimed toward reversing the effects of colonization” (1996). The fact that the jurisprudence of the Native Title Act has effectively replaced the doctrine of terra nullius by one of extinguishment is another important limit. According to this doctrine, the Australian courts and Parliament can legitimately extinguish indigenous rights and interests to land. It is in plain contradiction with some principles of international law, especially those that admit indigenous permanent sovereignty over their land and natural resources. (E/CN.4/Sub.2/2004/30).

Conflicts

The respect of indigenous peoples’ rights to land is in effect subordinated to the exploitation of natural resources, particularly minerals, which drives Australia’s economic growth. Several conflicts are currently underway regarding the location of a nuclear waste facility, the construction of a Liquefied natural gas (LNG) processing plant on the Kimberley shores and the protection of riverine ecosystems in far north Queensland. In each case the economic potential of the mining sector is in tension with environmental concerns and indigenous people’s rights and situation of entrenched poverty.

Perspectives

Despite its limits, the Native Title Act has instituted a right to negotiate for native title holders, opening up new possibilities such as Indigenous Land Use Agreements negotiated with State and third parties. The website Agreement, Treaties and Negotiated Settlement Project provides with a list of such agreement as well as many other information. Indigenous Protected Ares – national parks managed by traditional owners – are part of the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities’ Indigenous Australians Caring for Country programs.

Increased access to their lands has led Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to develop natural and cultural resource management programs, generally known as Caring for Country (for instance in the Top End) or “Looking After Country”. From local teams to a national conference, a national network of indigenous land managers is developing, pursuing other forms of sustainable development in rural and remote areas.

Culture

Language, education and culture | - 14 June 2011

Language, education and culture | - 14 June 2011

Languages of Australia

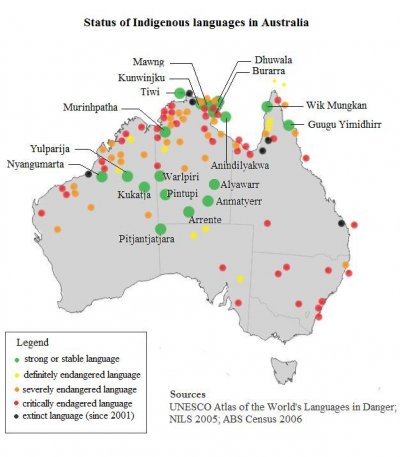

Linguists estimate that, at the time of colonial settlement, around 250 languages were spoken in Australia, with more than 500 dialectal forms. The impact of English settlement was very destructive to language diversity. The country has been described as among those that have seen the largest and fastest loss of language in the world during the 20th century. While 145 indigenous languages are still spoken in Australia, 110 are either severely or critically endangered, with only 18 considered strong/safe (NILS 2005, language resources on the web). Northern Australian Kriol and Torres Strait Broken are indigenous languages that emerged out of colonial contact and are widely spoken.

In 2009 the Commonwealth Government announced a “National Approach for Indigenous Languages” with no increase in funding from the Maintenance of indigenous Languages Records program. States and Territories are responsible for education and hence for language education. All of them have adopted indigenous language policies, and although there many problems hindering effective implementation, New South Wales’ policy and National language centre is generally presented as an example of good practice. In many cases, recording and transmission of indigenous languages are done by regional or local language resource centre or by indigenous communities. Interpreting and translation services for indigenous people remain largely underdeveloped, especially when compared to resources available for other Australians speaking a language other than English (see Social Justice Report 2009, chap. 3).

Education Rights

A significant gap in terms of access, retention and outcomes remains between indigenous and non-indigenous students in Australia. Educative achievement and access to employment are two main targets of the Closing the Gap policy. Each State and Territory have also adopted specific indigenous education policies (other resources on indigenous education).

Rights to education also include the right of indigenous peoples to an education in their own language and according to their systems of knowledge and teaching practices. Bilingual or two-way education was established in 1974 in the Northern Territory and some parts of Western Australia. Since then, there have been many debates among politicians and academics as to the relevance and success of such programs. The inclusion of indigenous languages and cultures within curricula depends on the States and on the autonomy given to local schools. Despite numerous studies showing their efficiency, bilingual programs have been under attack in the Northern Territory. On October 14, 2008, the then NT Minister for Education Marion Scrymgour announced that the first four hours of education in all NT Schools would be delivered in English. This effectively put an end to 34 years of Bilingual Education in the Northern Territory by ending the 10 remaining programs

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Cultures

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for at least 40 000 years, during which time they developed, and continue to live rich and diverse cultures (Torres Strait Islanders have lived on their country since at least 10 000 years). If the Dreaming (or Law) is a shared conceptual frame on the mainland, its local manifestations and the dynamic renewal of its cultural forms are indicative of societies where exchange and differentiation are highly valued.

Indigenous arts have acquired a wide visibility and international renown, especially since the 1970s. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders creators have explored all fields of creation: painting, sculpture, music, dance, cinema, theatre, literature, etc. Cultural festivals such as Garma, Laura or the Dreaming demonstrate the vitality of contemporary indigenous cultures drawing on ancestral sources. There are many other regional or local indigenous festivals in Australia. Each year, the best indigenous musicians, artists and sportspeople are celebrated at the Deadlys while the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Art Award rewards the best painters and sculptors.

Australian governments have actively promoted indigenous arts and cultures as a national heritage and an element of national identity since the 1970s in a spirit of reconciliation. This cultural and artistic recognition falls short, however, of a formal recognition of the people and societies which give rise to these cultural expressions