Research Areas | New Caledonia

Research project

Research project | - 12 July 2011

Research project | - 12 July 2011

Contexte

Depuis la fin des années 1980, les revendications en termes de décolonisation et d’indépendance en Nouvelle-Calédonie (territoire français du Pacifique Sud) ont provoqué dans le champ scientifique l’émergence de travaux originaux en anthropologie politique. Ceux-ci se sont tout particulièrement intéressés au militantisme nationaliste kanak (en faveur de la création de la « République de Kanaky ») puis aux processus de compromis et de réconciliation négociés entre Kanak, Caldoches (colons) et Etat français lors des Accords de Matignon (1988) puis de Nouméa (1998). Or depuis une dizaine d’années, de nouvelles revendications kanak ont vu le jour, qui se réfèrent explicitement à « l’autochtonie » et à la Déclaration des droits des peuples autochtones (DDPA/UNDRIP), plutôt qu’à l’indépendance ou la « citoyenneté calédonienne » prônée par l’Accord de Nouméa.

La présente recherche a pour vocation d’examiner la complexité des relations entre les idéologies et pratiques politiques kanak relevant de l’indépendantisme, d’une part, et de l’autochtonie, d’autre part. Ce débat renvoie en effet à une confrontation fondamentale entre deux types de légitimité politique kanak : celle des élus kanak (système représentatif d’inspiration occidentale) et celle des « coutumiers » (« chefs », « conseils des anciens », « sénateurs coutumiers »). Elles-mêmes nées de l’histoire coloniale, ces catégories « traditionnelles » nécessitent d’être dénaturalisées et restituées dans leur dynamique socio-historique propre.

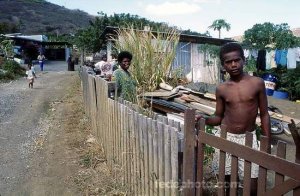

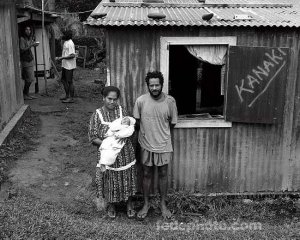

- Jeune famille kanake de la tribu de Montfaoué, devant leur maison, région de Poya, Province Nord, Nouvelle Calédonie. © Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

Deux stratégies politiques kanak pour l’auto-détermination

La Déclaration des droits des peuples autochtones a été votée par la France en 2007, alors que la Nouvelle-Calédonie se trouvait déjà à mi-parcours d’un processus inédit de décolonisation progressive défini par l’Accord de Nouméa (débuté en 1998 et qui se terminera entre 2014 et 2018). Cet Accord inclut notamment la reconnaissance d’institutions kanak autonomes : reconnaissance des « terres coutumières », promotion de la culture kanak, création « d’aires coutumières » et d’un « Sénat coutumier », reconnaissance de l’existence d’un « droit coutumier » (non écrit jusqu’à présent). Une « citoyenneté calédonienne » a également été créée par l’Accord de Nouméa, en tant que traduction légale, sociale et politique du concept fondateur de « souveraineté partagée dans un destin commun ». Depuis lors, certains activistes kanak ont mobilisé la DDPA/UNDRIP sur la scène politique locale, afin d’exiger un contrôle kanak global sur les ressources naturelles, ainsi qu’une écriture définitive du « droit coutumier ».

Notre recherche analyse la construction et les impacts de ces nouveaux discours et pratiques politiques kanak, qui renvoient pour une large part (mais pas uniquement) aux débats internationaux sur l’autochtonie. Nous étudions également les mécanismes de l’importation et de la circulation de ces débats internationaux sur la scène politique locale. Enfin cette recherche a également pour but de questionner le rapport de l’Etat français contemporain aux revendications de ces anciens « indigènes », qu’elles s’expriment en terme d’indépendance ou d’autochtonie. La Nouvelle-Calédonie fait ici figure de cas expérimental, que nous souhaitons également analyser dans une perspective comparative, au sein du programme SOGIP, notamment vis-à-vis de la Guyane Française

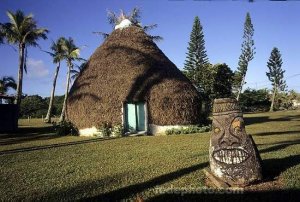

- Case kanake de la tribu de Xépénéhé, reportage à l’île de Lifou, province des îles, dans le cadre des bilans des Accords de Matignon, Nouvelle-Calédonie. ©Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

Les enjeux de l’alternative politique kanak

En matière de développement économique, les leaders kanak se revendiquant des droits autochtones s’appuient notamment sur l’article 29 de la DDPA sur la protection de l’environnement, afin d’exiger des dispositifs de compensation financière et des mesures environnementales face aux compagnies minières. En revanche, au nom de la « préparation à l’indépendance », les élus kanak des principaux partis indépendantistes soutiennent de nombreux projets de développement économique, devenant par là même des acteurs-clés du secteur stratégie de l’industrie du nickel.

- Ouvriers mineurs kanaks lors de l’extraction du nickel dans la mine de Ouaco, géré par La Province Nord, Province Nord, Nouvelle-Calédonie. ©Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

Plus largement, les leaders kanak nationalistes (FLNKS) et les leaders kanak « autochtones » (Rheebu Nuu, Caugern, Sénat coutumier) ont tendance à défendre désormais des perspectives politiques différentes concernant la place du peuple kanak au sein de la société calédonienne. Les élus du FLNKS jugent en effet que l’Accord de Nouméa a pleinement reconnu le principe des droits kanak, qu’il s’agit maintenant de mettre en œuvre et de concrétiser. De leur côté, les porte-parole de la « cause autochtone » considèrent que la reconnaissance des institutions coutumières (par l’Accord de Nouméa) permet désormais de revendiquer de nouvelles garanties légales, politiques et financières pour que les droits du peuple kanak soient respectés dans la société calédonienne, en dehors du cadre de la seule « citoyenneté calédonienne », et quelle que soit l’évolution statutaire du pays (indépendance ou maintien dans l’ensemble français). Ayant pour objet ces transformations politiques kanak contemporaines, notre recherche se focalise en particulier sur les usages et les non-usages de la DDPA/UNDRIP dans ce contexte politique troublé.

Data

General overview | - 12 July 2011

General overview | - 12 July 2011

General Demography

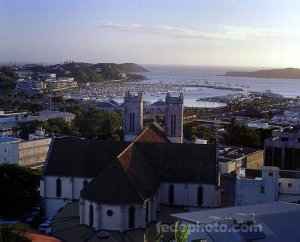

Located in the South Pacific, the French archipelago of New Caledonia holds a population of 245,580 inhabitants according to the 2009 census. Two-thirds of the population live in the only urban area of the territory, composed by the capital Noumea and three suburban cities, commonly called “the Greater Noumea”, in the south-west of the Grande Terre (main island). This demographic imbalance is also to be found across the three existing provinces: the Southern province, which includes the Noumea area, holds three-quarters of the population, while the Northern and Loyalty Islands provinces hold respectively 18% and 7% of the total population.

Indigenous Demography

The first inhabitants of New Caledonia were first called "Kanaks" (Polynesian word meaning “men”) by Tahitian translators of Captain James Cook when he discovered the archipelago (1774), then "Canaques" by the French administration when France took possession over the archipelago in 1853. This term gradually became pejorative and was officially replaced by the words "native", then "indigenous" or "Melanesian" from the 1950s. The first indigenous intellectuals of the 1970s turned the stigma of the word "Canaque" into a symbol of identity and political pride as they restored and used the original English spelling "Kanak". The Noumea Accord of 1998 has officially recognized this terminology.

Facing French colonial settlement policies from the mid-nineteenth century, the Kanaks still accounted for half of the total population in 1950. In the early 1970s, the influx of new residents placed the indigenous population in a minority position for the first time ever (40% of the population). According to the 2009 census, 44% of inhabitants identify themselves today as Kanaks (mixed race or not), 34% as Europeans (mixed race or not) and 10% as Wallisians-and-Futunans (mixed race or not). The rest of the population is divided between other "communities" (Tahitian, Indonesian, Vietnamese, ni-Vanuatu, other Asian, other). In the previous census (2004), no question about community membership had been raised because of the virulent debate on ethnic data occurring at that time in metropolitan France. It raised an important issue to measure the effectiveness of official rebalance policies in favour of the Kanaks. Ethnic questions have been reintroduced in the 2009 census.

The rural Northern and Loyalty Islands provinces are mostly inhabited by Kanaks (about 80% in the North and nearly 100% in the Loyalty Islands). About half of the Kanak population is now installed in the urban area of "the Greater Nouméa" in the Southern province.

Political and legal regime

New Caledonia is a former Overseas Territory of the French Republic (Territoire d’Outre-Mer). Since 1998, it has become a specific French territory (“collectivité sui generis”) engaged in an unprecedented decolonization process under the Noumea Agreement. This text, which sets the political framework of New Caledonia until 2014, has been integrated within the French Constitution (articles 76 and 77). It organizes a progressive and irreversible transfer of power from the French State to the local Government of New Caledonia, the latter being an executive body formed by proportional representation of the main political groups in the Congress of New Caledonia (on Caledonian institutions, see here). Between 2014 and 2018, a local referendum shall be held to decide whether or not the remaining sovereign powers (defense, public order, justice, currency, external relations) will be transferred to New Caledonia. A positive response would lead the archipelago to full sovereignty.

The Congress of New Caledonia has a quasi-legislative power, as it votes "laws of the country" (“lois de pays”). It is formed by provincial elected members from the three provinces, elected every five years by all "Caledonian citizens". Created by the Noumea Agreement, this last category brings together all French citizens settled in New Caledonia before November 8, 1998 and proving ten years of residence, and their descendants. The three Provinces, which hold broad responsibilities and important financial powers, were created in 1988 to ensure, through decentralization and electoral delimitation, a real sharing of power between pro-independence Kanaks (representing an electoral majority in the Northern and Loyalty Islands provinces) and anti-independence non-Kanaks (a majority in the Southern Province). So far, the chairmanships of Congress and government have always been insured by Europeans anti-independentists, while the vice-presidency of the Government is traditionally hold by a pro-independence Kanak leader.

On the French national scale, there are four Members of Parliament elected in New Caledonia: two in the National Assembly and two in the Senate. At the municipal level, New Caledonia is composed of thirty-three French municipalities. The French Government is represented in New Caledonia by the High Commissioner of the Republic.

Socio-economic data

Most institutions and administrations of New Caledonia do not produce statistics on ethnic lines, so it is quite difficult to have access to socio-economic data regarding the specific position of the indigenous Kanak population within the broader New Caledonian society.

In the only jailhouse in the country, the Kanak represent approximately 80% of inmates. All Pacific Islanders (Kanaks, Wallisians and Futunans, Polynesians, Ni-Vanuatu) constitute 90% of inmates. Because of the dilapidation and overcrowding of the institution, European parliamentarians who visited the prison in January 2010 called it "the most putrid prison of the French Republic" (Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 7 and 12 January 2010).

The wealth gap in New Caledonia is much more pronounced than in France: in the city of Noumea, the 10% poorest households earn on average 13 times less than the 10% richest households, while this ratio is 1 to 5 in France (Alain Decombel and Gaël Lagadec, L’ombre de la crise, 2009, p. 151). According to a recent statistical study conducted across the Northern Province, given equal status (same age, same sex, same qualification), Kanaks earn on average 32% less than non-Kanaks (Osas, Etre jeune en Province Nord, 2010, p. 5).

According to a statistical survey of the INSERM (Christine Hamelin and Christine Solomon, 2008) conducted on the health behavior of young people in New Caledonia, 79% of the young metropolitans over 21 living in New Caledonia gratuated from high school (hold a baccalauréat), versus 67% of the Caledonian Europeans, 49% of the Polynesians and only 34% of the Kanaks. In metropolitan France and overseas, in 2007, the global rate of high school graduates (holders of a baccalauréat) for a generation reached 63.8%.

Regional context

Regional and global context | - 13 July 2011

Regional and global context | - 13 July 2011

Located at the antipodes of the Hexagon, New Caledonia is part of the French Republic and the European Union. It is one of the three French territories of the Pacific, along with French Polynesia and Wallis-and-Futuna. There are numerous familial, economic, religious and educational ties between New Caledonia and these two French territories, but also between New Caledonia and Vanuatu, the neighboring archipelago and former Franco-British colony until 1980.

Within the Pacific Islands Forum, which brings together the 16 independent countries of the Pacific (including Australia and New Zealand), New Caledonia has been invited as an observer from 1999, then as an associate member since 2005. Regarding links between France, New Caledonia and the Pacific Islands Forum, see here.

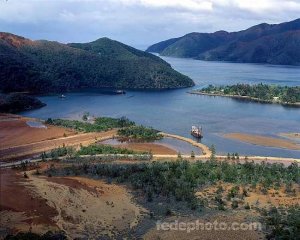

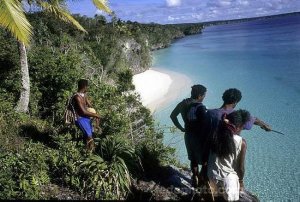

- Beach of kiki, tribu of Xépéhéné, reportage on island of Lifou, province des île. photograph © Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

The Melanesian Spearhead Group is a political group that includes “brother countries” of Melanesia, namely the independent states of Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Fiji, as well as the Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS, Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front), which is the main pro-independence Kanak coalition in New Caledonia. Within this lobbying group traditionnally advocating the Kanak pro-independence struggle in regional and international arenas, the issue of the replacement of the FLNKS by the Government of New Caledonia is currently the subject of considerable debate.

The Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) is an international institution bringing together the independent states and the non-independent territories of the Pacific region, including New Caledonia. Its headquarters are based in Noumea.

Rights

Rights, law and Politics | - 13 July 2011

Rights, law and Politics | - 13 July 2011

The issue of independence

In 1946, the Kanaks, formerly defined as ‘native subjects’ of the French Empire, obtained French citizenship. As French citizens, they had the right to vote from the 1950s (in municipal, territorial, legislative, presidential, European, and provincial elections). Since the 1970s, the emergence of a new claim for Kanak independence has created a strong polarization, both political and ethnic. – The vast majority of pro-independence activists were Kanaks, while the anti-independence sympathisers included most of the non-Kanak population (Europeans, Wallisians, Indonesians, etc.). This political and racial division is still visible today. On the transformations of the political field in relation to the Kanak struggle, see for instance the articles of Benoît Trépied and Christine Demmer.

The claim for independence arose in the 1970s and 1980s, in a context of demographic minorization for the Kanaks. This situation represented an unprecedented problem with respect to the political basements of the French Republic. Because of the fundamental principle of non-discrimination among French citizens, it is indeed anti-constitutional to hold a referendum on independence for just one particular category of the New Caledonian population (ie the Kanaks). As the majority of French citizens living in New Caledonia are hostile to the archipelago’s independence, the result of a referendum with no electoral discrimination would be automatically negative, which would lead to the non-recognition of the legitimacy of the Kanak claim for independence. However, the Kanak legitimacy is rooted in the denounciation of European colonization and settlement, and it requires a true process of decolonization – which meant, for the Kanak activists of the 1980s, the country’s accession to full independence. This opposition between French legitimacy and Kanak legitimacy led to violent clashes between Kanak independentists and European "loyalists" in 1984-1988 (commonly named "les événements" – the events).

As the French State refused to recognize the Kanak claim for independence, the Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS, Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front) adopted an important diplomatic strategy in the international arena throughout the 1980s. With the active support of independent countries from the Pacific (especially the Melanesian States forming the “Melanesian Spearhead Group”), and despite active opposition of French diplomats, the FLNKS managed to have New Caledonia registrered on the list of non-sovereign countries compiled by the United Nations Decolonization Committee in December 1986.

In 1988, a compromise was found to stop the violence and allow the return of the peace in the archipelago: the Matignon-Oudinot Agreement. It was negociated and signed by the French Government, the FLNKS, and the Rassemblement pour la Calédonie dans la République (RPCR, Coalition for Caledonia within the Republic, the main anti-independence party). According to this agreement, a referendum on self-determination was organized in 1998, after a delay of ten years. The agreement also initiated important measures of socio-economic rebalancing in favor of the Kanaks (on infrastructure, economic development, health, education, land, culture, etc.), and a real sharing of political power through decentralization and the creation of three Provinces; due to electoral delimitation, the Northern Province and the Loyalty Islands Provinces are automatically dominated and ruled by pro-independence Kanak leaders. In November 1988, the Matignon-Oudinot Agreement has been approved by a majority of French citizens (in metropolitan France and over-seas) on a national referendum.

In 1998, the FLNKS, RPCR and the State began new negotiations to find a new political agreement to replace referendum on self-determination originally scheduled by the Matignon-Oudinot Agreement. They settled a compromise, the Noumea Agreement, which organized the progressive decolonization of New Caledonia over a period of 15 to 20 years. The Noumea Agreement is based on a series of unprecedented measures: primary recognition of Kanak identity; creation of a collegial Government of New Caledonia; creation of a “citizenship of New Caledonia” within the French citizenship; establishment of a social project of "common destiny" for all “Caledonian citizens”; gradual and irreversible transfer of power from the French State to the Government of New Caledonia; restricted access to the Caledonian electorate roll; protection laws on local employment; and finally upcoming referendum of self-determination scheduled between 2014 and 2018. The Noumea Accord has been approved by local referendum in New Caledonia, and integrated into the French Constitution (articles 76 and 77).

The issue of “indigeneity”

During the colonial period (1853-1946), Kanak individuals were not officially identified: the French administration only identified “native tribes”. Within the colonial terminology, a “tribe” referred to a group of natives officially represented and led by a “chief” (appointed and paid by the administration). Each tribe owned collectively a piece of land, called a “native reserve”. The French notion of “chief” was far from reflecting the complexity and intricacies of power relationships and other networks of influence which characterized the Kanak society. Some administrative “chiefs” did benefit from pre-existing positions of power within the Kanak world, while others owed their political rise only to their official status as native authorities within the colonial framework. When the extension of French citizenship from the 1950s led to the election of Kanaks within democratic institutions (municipalities, the Territorial Assembly, provinces, etc), the effective political power of the “chiefs” declined, to the benefit of the new Kanak elected members.

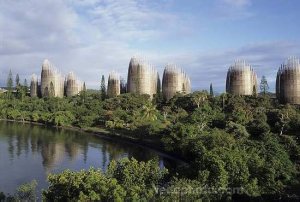

- Octave Togna, director of ADCK, is preparing for the opening of the du cultural centre, Centre culturel kanak Jean-Marie Tjibaou "Ngan Jilia", by architect Renzo Piano, Nouméa, Province Sud, Nouvelle-Calédonie. photograph © Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

Among their various demands, the Kanak leaders of the FLNKS asked for the recognition of the "customary authorities". In 1988, the Matignon-Oudinot Agreement created the Conseil Consultatif Coutumier (Customary Advisory Council), as well as 8 "customary areas" (5 on the mainland and 3 in the Loyalty Islands), delimitated with respect to languages and/or traditional social organization. In 1998, the Noumea Agreement reaffirmed the importance of these customary areas and turned the Customary Advisory Council into a Sénat Coutumier (Customary Senate), whose opinion must be requested by the Congress of New Caledonia for any law dealing with Kanak identity. Within each “customary area”, the members of the “customary area bureau” represent all administrative “chiefdoms” included in the territory. Although the Nouméa Agreement gives no specific indication on the designation process, the Kanak representative members of the Customary Senate and of the 8 customary areas are usually chosen by consensus. The members of the Customary Senate are urging an increase in their powers and skills; however this issue is clearly not a priority for elected politicians, neither Kanak independentists nor European “loyalists”.

As a legacy of the colonial period, article 75 of the French Constitution recognizes the existence of a particular civil law for certain French citizens who are not subject to the Civil Code (Kanaks, Mahorais from Mayotte island, Wallisians-and-Futunans). The Noumea Agreement states that this particular civil law, reclassified as “Kanak customary law”, must be written and codified. Since the 2000s, members of the Customary Senate and other spokespersons of “customary authorities” have requested new policies on this matter. Among other arguments, they rely on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples voted in 2007. This “neo-customary” Kanak political strategy relies therefore directly on international debates related to the “indigenous issues”: it states that decolonization should now result in new collective rights reserved to the Kanaks. In other words, the “indigenous strategy” increasingly differs from the FLNKS strategy, whose definition of decolonization refers to independence and the construction of "common destiny" within the “Caledonian citizenship”. On the emergence of the issue of “indigeneity” in New Caledonia, see articles of Christine Demmer, Natacha Gagné and Marie Salaün.

- Pro-independence “Kanaky” Flag., inside housing, kanak family living in a squatt at Logicoop at Ducos, reportage in the city of Nouméa. photograph © Jean-François Marin/fedephoto.com

Intellectual property rights are among these new “indigenous rights” about to be debated in the Caledonian political arena. In 2010, the Government of New Caledonia created a policy committee dedicated to the regulation and protection of traditional knowledge and indigenous intellectual property rights. A “loi de pays” (local law act) on this matter is scheduled to be discussed by the Congress of New Caledonia during year 2011.

Territory

Land, territory and resources | - 13 July 2011

Land, territory and resources | - 13 July 2011

"Native reserves"

At the end of the great land dispossession process which took place in the nineteenth century to allow the European settlement, the land officially allocated to the indigenous population only represented about 8% of the Grande Terre (main island). The Kanaks were mostly displaced and relocated in remote areas with poor soils, while all the best agricultural land was taken over by settlers. This imbalance between Kanak lands and European lands remained largely unchanged until the 1970s, despite a few modest “reserves extensions” in favor of the Kanaks in the 1950s and 1960s.

During the colonial period, land plots allocated to the Kanaks were officially called "native reserves". These reserves, until today, are legally inalienable, incommutable and unseizable. Unlike the Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, which have experienced administrative colonization but no European settlement, have a status of full native reserves. The administration has precisely defined the boundaries of the reserves, but never intervened in the internal management of these areas. As a result, there is no official cadastre within the reserves, nor any other administrative zoning (no “Plan d’urbanisme directeur”, etc). The Kanaks do recognize particular forms of land ownership and various uses of land inside the reserves, but all these rules are not written and remain below the official administrative level.

Land reform

In the 1970s, the pro-independence Kanak activists demanded the return of dispossessed land. They organized numerous land occupations on European properties, which caused several clashes between Kanaks and settlers. In 1978, the French State launched a global land reform, still going on today. This new land policy has been directed by several public agencies, the latest being the Agence de Développement Rural et d’Aménagement du Foncier (ADRAF, Land and Rural Development Agency).

The basic principle of the land reform is for the ADRAF to buy land to settlers and redistribute it to relevant Kanak clans or tribes. This is not a judicial process (there is no case argued in court) but rather an administrative mechanism, based on specific investigations conducted by the staff of the ADRAF. Land allocations are subject to prior consensus within local Kanak communities. They are mainly attributed to Groupements de Droit Particulier Local (GDPL, Particular Civil Law Corporations) representing Kanak clans or tribes. Since the Noumea Agreement, GDPL lands and reserve lands are officially designated under a single category: “customary land”. Overall, customary land now accounts for about 18% of the total area of the Grande Terre. The ADRAF website provides details on customary land mapping.

Resources

New Caledonia is identified as a “hotspot” of global biodiversity. Its lagoon was declared a World Heritage Site by the Unesco in 2008. This dynamic of patrimonialization of the Caledonian nature and environment raises important social issues (on this topic, see the article of Elsa Faugère).

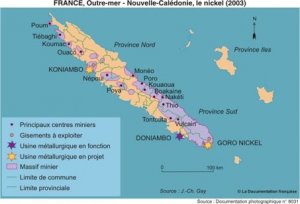

New Caledonia holds about 25% of the world’s known reserves in nickel. Until recently, the Société Le Nickel (SLN, a subsidiary of Eramet controlled by the French State) reigned entirely over the New Caledonian nickel industry. The Kanaks have long been kept out of the profits from extractive industries, while the Kanak tribes located near mining sites have been repeatedly confronted to mining pollution.

In 1990, the FLNKS Kanak leaders at the head of the Northern Province acquired the Société Minière du Sud Pacifique (SMSP, South Pacific Mining Society) through the Société d’Investissement Financière de la Province Nord (Sofinor, investment company of the Northern Province). Since then, they have initiated a major industrial and urban development project in the North, based on the construction of a great metallurgic factory (the “Northern Factory”). This project eventually became the flagship project of the pro-independence movement, as it is seen as a way to counterbalance the power of Noumea and the Southern Province, and to propose an economically viable independence. Currently under construction, the "Northern Factory" is jointly owned by the SMSP (51% of the capital) and a large multinational corporation specialized in nickel metallurgy (Xstrata, 49% of capital). This project is linked to the exploitation of the rich mines of the Koniambo mountain, whose ownership has been transferred from the SLN to the SMSP in 1996 after tough negotiations, commonly known as “the mining prerequisite” (many barricades and demonstrations led by pro-independence activists; on this issue, see the article of Leah Horowitz).

At Yaté, on the southern tip of the Grande Terre, another major nickel factory (Goro Nickel) has been built by Vale Inco, in partnership with the Southern Province, from 2001. Unlike the “Northern Factory” issue, the Kanak inhabitants of Yaté have not been associated with the “Southern Factory” project. They have suffered significant environmental damage, which has resulted in a strong local mobilization against Goro Nickel, including many cases argued on court and physical confrontation. On these occasions, several environmentalist associations and Kanak “customary authorities” of Yaté have called for the respect of indigenous rights, to force Vale Inco and the Southern Province to negociate. A compromise was finally signed in September 2008. However, there are still many concerns, among the Kanak population of Yaté, regarding environmental hazards and the respect of the rights of local inhabitants (see again the work of Leah Horowitz).

Culture

Language, education and culture | - 13 July 2011

Language, education and culture | - 13 July 2011

Languages

28 Kanak languages are spoken in New Caledonia, all related to the Austronesian language family, as well as a creole (the tayo) spoken by a Kanak tribe located near Noumea. Nowadays, all speakers of Kanak languages also speak French, as French is the only vehicular language of the country. Long banned in public in favor of French, previously the only official language of the Territory, the Kanak languages have acquired an official status since 1998 with the Noumea Agreement, which states: "Kanak Languages are, with French, languages of education and culture in New Caledonia. Their place in education and in the media should be increased and be subject to careful consideration. " (Nouméa Agreement, point 1.3.3).

A department of "Kanak languages and culture" has been established at the University of New Caledonia in the early 2000s. It trains students (mostly Kanak) for positions as Kanak language teachers or specialists hired by the Academy of Kanak Languages, an institution created in 2007 in the wake of the Noumea Agreement. In 2006, the Congress of New Caledonia has set education in Kanak languages (optional, not mandatory) to 5 hours per week in primary schools. As for collèges (junior high schools) and lycées (high schools), some of them offer Kanak language courses, depending on local conditions, but without a comprehensive policy at the territorial level. An optional test in Kanak languages is scheduled at the baccalauréat (high school final examination). Despite these initiatives in education, the Kanak languages are very poorly represented in the media and in the public arena throughout the country (for details, see here).

Education

Until after the Second World War, colonial education for the indigenous population was strictly separated from settlers’ schools, with no possibility of access to secondary education for Kanaks. The first Kanak who passed the baccalauréat was recorded in 1962, and the first Kanak graduating at the university in the late 1960s. The Kanak revolt of the 1980s was also deployed in the field of education (denouncing the “French colonial school"), which led to the creation of "Kanak Popular Schools" (EPK). After the return of peace in the 1990s, these alternative Kanak schools have gradually closed their doors one after the other, as the French school system became once again the unchallenged standard of "success" in education. While the overall level of training has constantly increased over the last thirty years, educational inequalities persist between communities: according to the 2009 population census, 54% of the Europeans have passed the baccalauréat, versus 12% of the Kanaks. One young European out of two has gratuated in higher education, versus one out of 20 within the Kanak and Wallisian communities and. On widespread culturalist clichés regarding Kanak difficulties in education, see for instance the writings of sociologist Marie Salaün.

- Internat Juvenat de Nouville, soutien scolaire aux lycéens kanaks, reportage dans la ville de Nouméa. ©Jean-François Marin/Fédéphoto.com

Culture

Long despised, the Kanak culture has experienced a strong re-appreciation since the 1970s, in the wake of the Kanak political struggle for decolonization and independence. Created by the Matignon Agreement in 1988, the Kanak Culture Development Agency (ADCK) is specifically dedicated to the promotion of Kanak culture across the country. Among other things, the ADCK runs the Tjibaou Cultural Center, a vast cultural complex located in Noumea, inaugurated in 1998 and built by world-known architect Renzo Piano. Although Kanak contemporary artistic expression (in music, dance, sculpture, painting, theater, literature) is now fully recognized and supported on the institutional level (by the ADCK, the provincial cultural centers, copyright system, musical scenes, etc.), meaningful recognition of practical forms of Kanak identity and culture in daily social life (work, school, housing, transport, urban life…) remains largely uncompleted. The dominant social norm, especially in the “Greater Nouméa” which concentrates three-quarters of the population of New Caledonia, is still the French culture.

Version imprimable

Version imprimable